Why is the sky blue?

Let’s start by asking ourselves: what color SHOULD the sky be?

Or, one step further back, what color should anything be?

And the answer is: the color of anything is due to[1] the wavelength of photons coming from that thing and hitting your eye.

Well ackshually… 🧐

These sidenotes are optional to read, but I’ll use them for giving the fuller technical details when I’ve abbreviated things in the main body of the text.

In this case, the color you see is determined by the wavelengths of light entering your eye since (1) you may be seeing a pure frequency, but in almost all cases, (2) you’re seeing many frequencies, which your brain interprets as a single color.

For instance, the sensation of turquoise at a specific point can be caused by (a) photons of wavelength 500nm emanating from that point, (b) a specific combo of photons of wavelengths 470nm and 540nm, or (c) (mostly realistically) photons of a huge number of wavelengths, probably peaking somewhere around 500nm.

In the text, I am a bit fast and loose with the difference.

When sunlight hits Earth’s atmosphere, most colors of photons pass through unencumbered. But blue photons have a tendency to ricochet around a lot.

This causes them to disperse all throughout the atmosphere. They disperse so far and wide, and are so numerous, that you can look at any part of the sky on a clear afternoon and, at that moment, blue photons will be shooting from that point straight to your eyes.

Therefore the sky is blue.

What’s so special about blue?

This is true and all, but it kicks the can down the road. Why blue? Why not red?

In short, it’s because blue and violet have the closest frequencies to a “resonant frequency” of nitrogen and oxygen molecules’s electron clouds.

There's a lot there, so we'll unpack it below. But first, here's an (interactive) demo.

When a photon passes through/near a small molecule (like N2 or O2, which make up 99% of our atmosphere), it causes the electron cloud around the molecules to “jiggle”. This jiggling is at the same frequency as the photon itself – meaning violet photons cause faster jiggling than red photons.

In any case, for reasons due the internal structure of the molecule, there are certain resonant frequencies of each molecule’s electron cloud. As the electron clouds vibrate closer and closer to these resonant frequencies, the vibrations get larger and larger.

(This is completely analogous to pushing a child on a swing at the “right” frequency so that they swing higher and higher)

The stronger the electron cloud’s oscillations, the more likely a passing photon (a) is deflected in a new direction rather than (b) passes straight through.

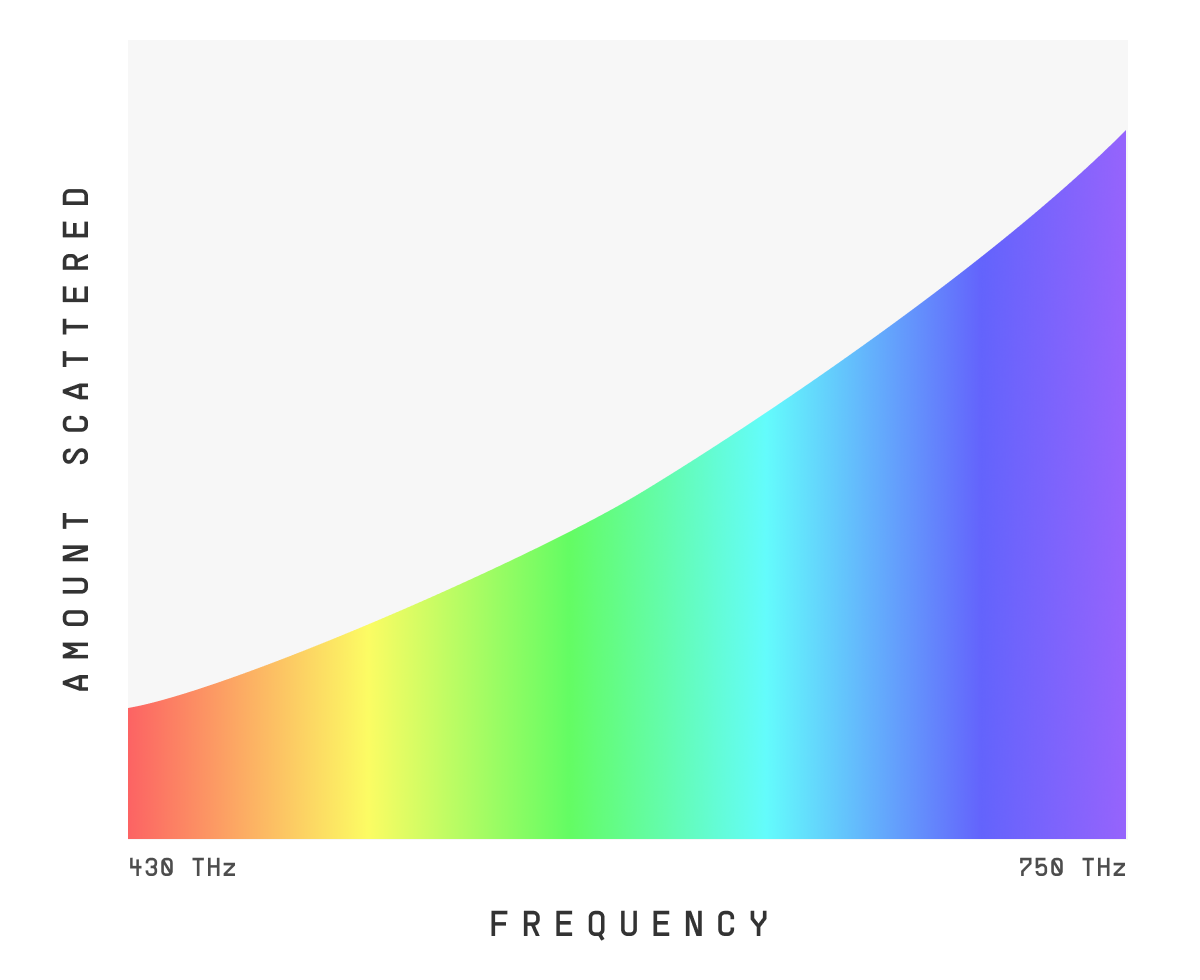

For both N2 and O2, the lowest resonant frequency is in the ultraviolet range. So as the visible colors increase in frequency towards ultraviolet, we see more and more deflection, or “scattering”[2].

“Scattering” is the scientific term of art for molecules deflecting photons. Linguistically, it’s used somewhat inconsistently. You’ll hear both “blue light scatters more” (the subject is the light) and “atmospheric molecules scatter blue light more” (the subject is the molecule). In any case, they means the same thing 🤷♂️

In fact, violet is 10x more likely to scatter than red.

So why isn't the sky violet? Great question – we'll cover that in a sec.

I just want to point out two other things that (a) you can see in the demo above, and (b) are useful for later in this article.

First, when light gets really close to – and eventually exactly at – the resonant frequency of the molecule’s electron cloud, it gets absorbed far more than scattered! The photon simply disappears into the electron cloud (and the electron cloud bumps up one energy level). This isn’t important for understanding the color of Earth's sky… but there are other skies out there 😉

Second, did you notice that even red scatters some? Like, yes, blue scatters 10x more. But the sky is actually every color, just mostly blue/violet. This is why the sky is light blue. If white light is all visible colors of light mixed together equally, light blue is all visible colors mixed together – but biased towards blue.

What would the sky look like if it was only blue? Check it out.

I'll just end by saying, this dynamic (where scattering increases sharply with the frequency of light) applies to far more than just N2 and O2. In fact, any small gaseous molecule – carbon dioxide, hydrogen, helium, etc. – would preferentially scatter blue, yielding a blue sky at day.

Why isn’t the sky violet?

As you saw above, violet scatters more than blue. So why isn’t the sky purple? The dumb but true answer is: our eyes are just worse at seeing violet. It’s the very highest frequency of light we can see; it’s riiight on the edge of our perception.

But! – if we could see violet as well as blue, the sky would appear violet.

We might as well tackle the elephant in the room: if we could see ultraviolet (which is the next higher frequency after violet), would the sky actually be ultraviolet?

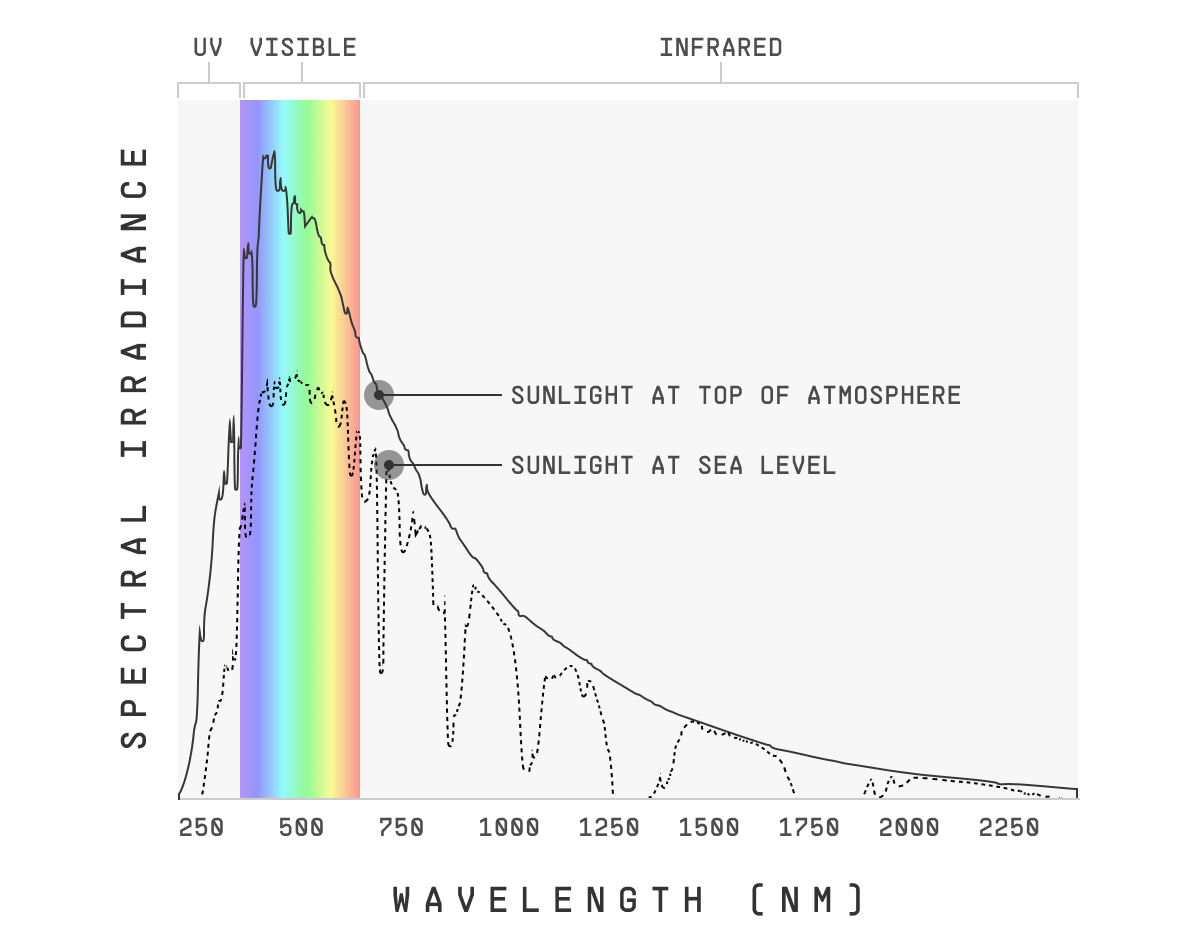

And the answer is not really. If we could see UV, the sky would be a UV-tinted violet, but it wouldn’t be overwhelmingly ultraviolet. First, because the sun emits less UV light than visible light. And second, some of that UV light is absorbed by the ozone layer, so it never ever reaches Earth’s surface.

You can see both of those effects in the solar radiation spectrum chart:

Why is the sunset red?

So the obvious next question is why is the sky red at dusk and dawn?

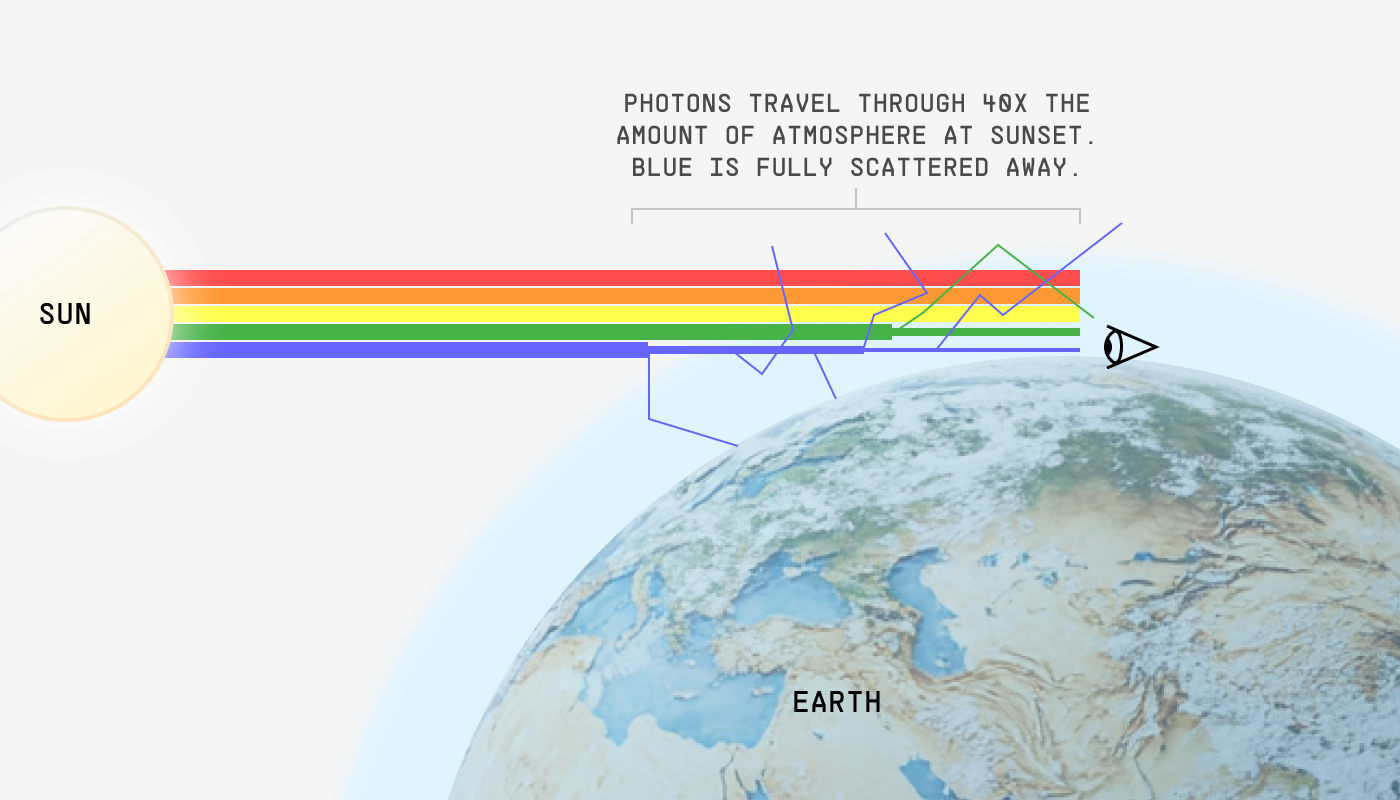

It’s because the sunlight has to travel through way more atmosphere when you’re viewing it at a low angle, and this extended jaunt through the atmosphere gives ample opportunity for allll the blue to scatter away – and even a good deal of the green too!

Simply put, the blue photons (and to a lesser degree, the green) have either (a) gone off into space or (b) hit the earth somewhere else before they reach your eyes.

When the sun is on the horizon (e.g. sunrise or sunset), the photons it emits travel through 40x as much atmosphere to reach your eyes as they would at midday. So blue’s 10x propensity to scatter means it’s simply gone by the time it would’ve reached your eyes. Even green is significantly dampened. Red light, which hardly scatters at all, just cruises on through.

Again, you can play with this and see for yourself 😎

Why are clouds white?

The answer to this question is the second of three “domains” you should understand in order to have a working model of atmosphere color. The physics are different from the small-molecule scattering above.

Clouds are made up of a huge number of tiny water droplets[3]. These droplets are so small (around .02 millimeters in diameter) that they remain floating in the air. But compared to small gas molecules like N2 and O2, these droplets are enormous. A single water droplet may be 100 trillion H2O molecules!

A small cloud may be a quadrillion droplets.

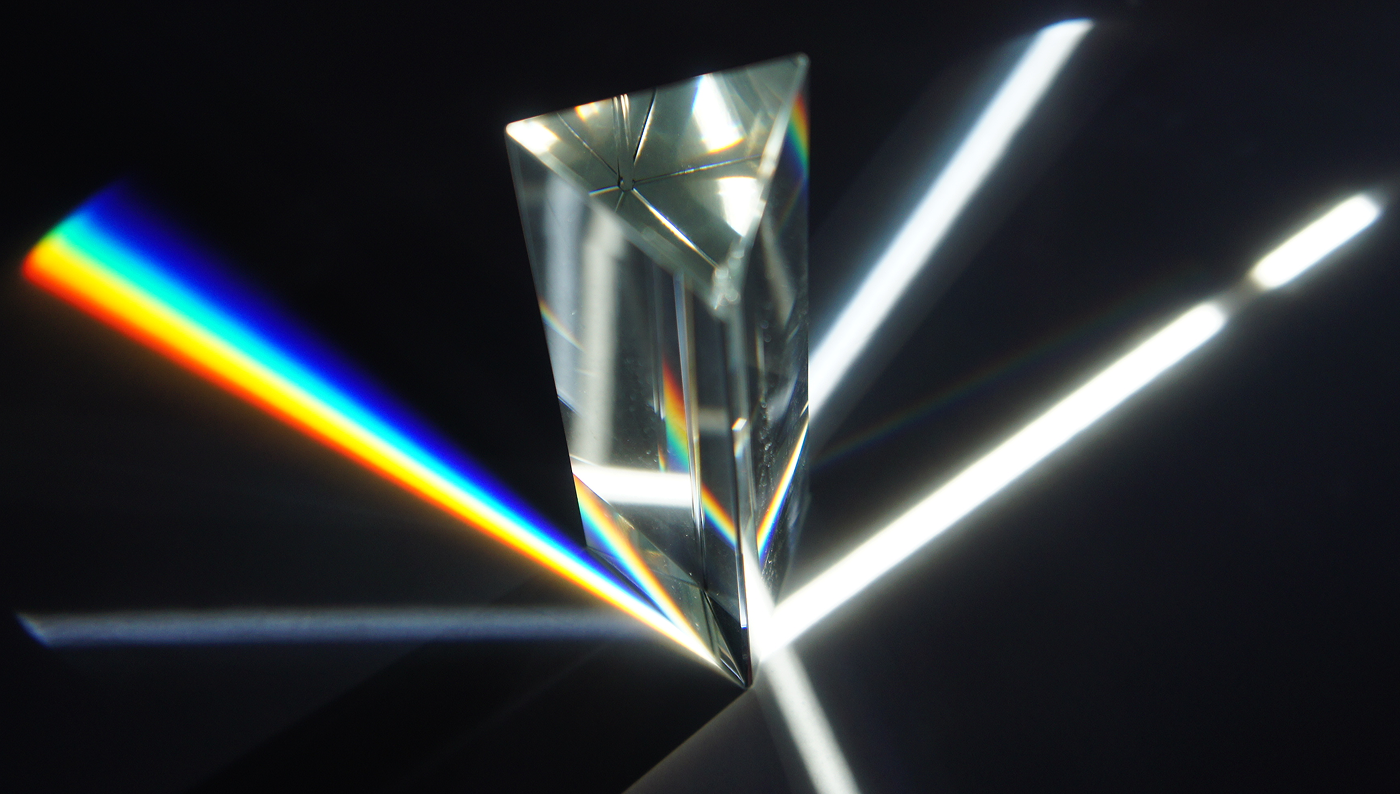

So, it’s not as simple as “the photons cause the hundreds of trillions of electrons to jiggle”. Instead, it’s more like the light has entered a very tiny prism or glass bead.

The droplet is just as complex. Some of the photons hitting the droplet bounce off the surface. Some enter it, bounce around inside once, twice, etc. – and leave again. Perhaps a few are absorbed. As with a prism, different wavelengths of light will reflect at different angles. The specifics aren’t important – you should just get the general gist.

So whatever white (or slightly yellowish) light that came from the direction of the sun is leaving in many random directions. Think of every color, shooting off in different directions! And then multiply that by a quadrillion droplets! In sum, you just see every frequency of photon coming from every part of the cloud.

And that means the cloud is white!

This idea that the tiny droplets that comprise clouds scales up. Anything larger that light can enter – drizzle, raindrops, hail – will also tend towards white.

But that raises the question – what about things in between tiny molecules (N2, O2) and the relatively enormous prism-like droplets? How do those things act?

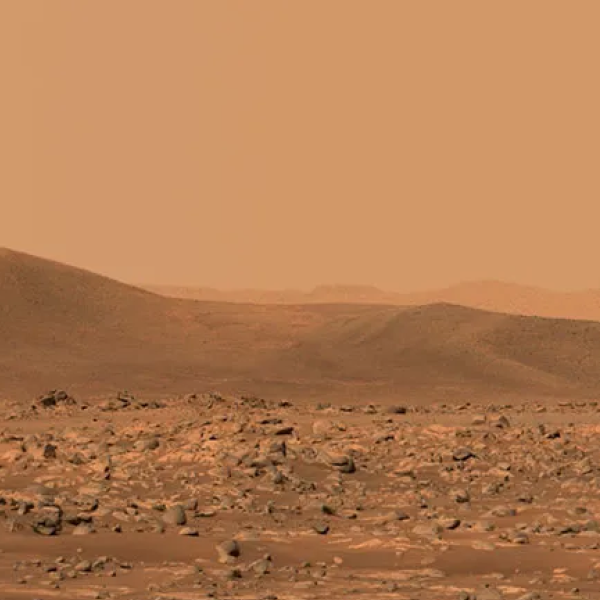

Well, the dust in the sky of Mars is a great example 😉

Why is the sky on Mars red?

The answer to this question is the third of three “domains” you should understand in order to have a working model of atmosphere color. The physics are different from both the small-molecule scattering and large-droplet prism-dynamics above.

The Martian sky is red because it’s full of tiny, iron-rich dust particles that absorb blue – leaving only red to scatter.

Yeah, yeah, I hear you. This answer is can-kicking! “Dust, schmust. Why does it absorb blue?”, you demand.

OK, so the answer is actually fairly straightforward. And it generalizes. Here’s the rule: whenever you have solid particles in the atmosphere (very small ones, approximately the size of the wavelength of visible light), they generally tend to turn the air warm colors – red, orange, yellow.

If you live in an area with wildfires, you’ve probably seen this effect here on Earth!

To really understand the reason, let’s back up and talk about some chemistry.

Compared to tiny gas molecules, solid particles tend to have a much wider range of light frequencies that they absorb.

For instance, we discussed how N2 and O2 have specific resonant frequencies at which they hungrily absorb UV photons. Move slightly away from those frequencies, and absorption drops off a cliff.

But even for a tiny dust nanoparticle, there are many constituent molecules, each in slightly different configurations, each being jostled slightly differently by its neighbors. Consequently, the constituent molecules all have slightly different preferences of which frequency to absorb.

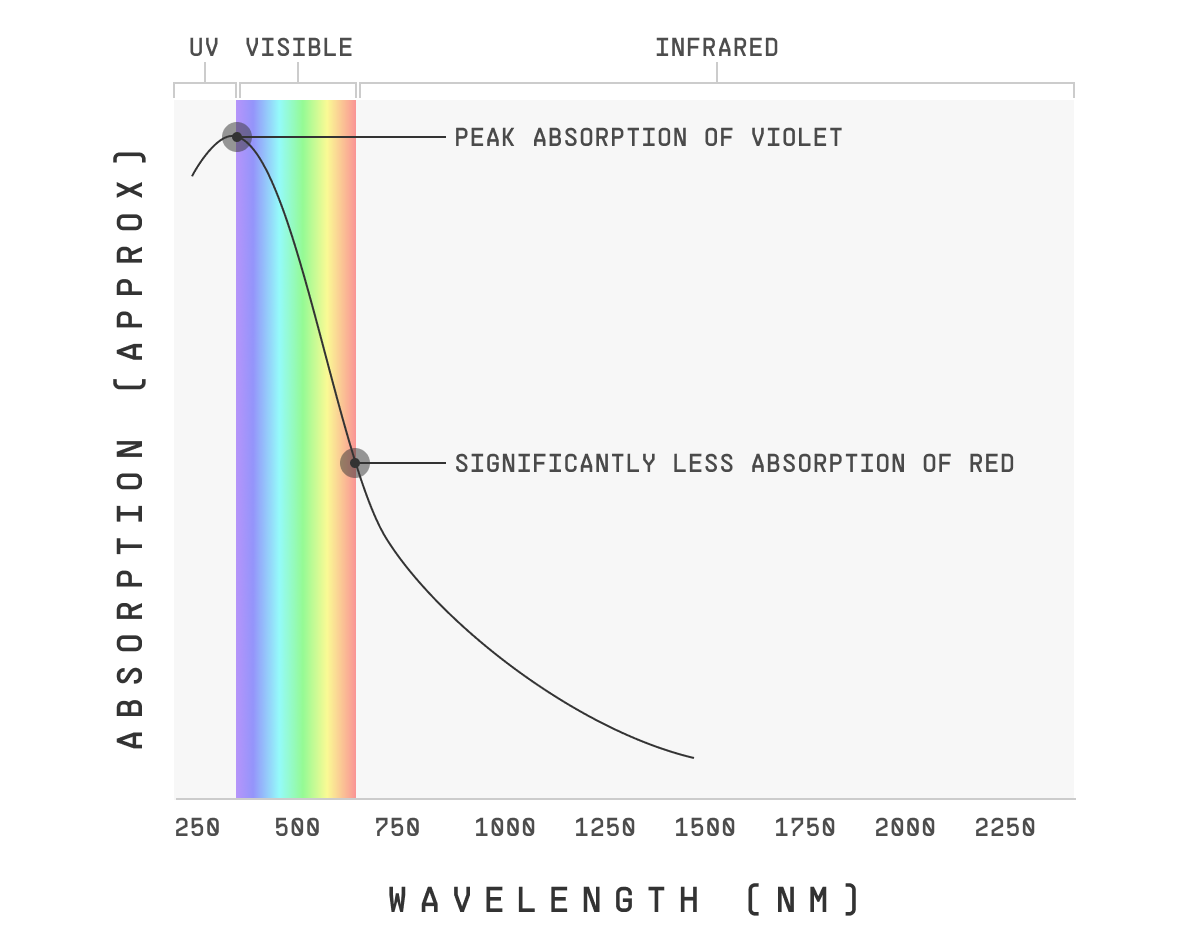

Because the “peak” absorption of the molecules is usually violet or ultraviolet (as it is with small gases), blues/violets will make it to the surface much less than oranges/reds.

Of course, a reasonable question is why are blue and violet absorbed so strongly by these dust particles?

Well, those are the only photons with enough energy to bump the dust molecules’s electrons up to a new energy state.

(Reminder: a photon’s energy is proportional to its frequency. Higher frequency – e.g. violet – means higher energy, and lower frequency – e.g. red – means lower energy)

So, the exact specifics depend on the molecules in question, but generally, the level of energy needed to bump up the electron energy state in a dust or smog particle’s molecules corresponds to violet or UV photons.

This is actually true of solids in general, not just atmospheric dust or aerosols. If you’ve ever heard that purple was “the color of kings” or that the purple dye of antiquity was worth its weight in gold, it’s true! To get something purple, you’d need to find a material whose electrons were excited by low-energy red photons, but had no use for higher-energy violet photons.

So this is why the Martian sky is red – and why reds and browns are more common in nature (for solid things, at least) than purple and blue.

Why is the Martian sunset blue?

It’s less famous than the red daytime sky of Mars, but the Martian sunset is blue!

Photo by NASA/JPL/Texas A&M/Cornell.

In the last section, we talked about Martian dust absorbing violet/blue. But the dust also scatters light – which it can do totally unrelated to how it absorbs (remember, since photons can – and usually do – cruise straight through a molecule, scattering and absorbing can have their own interesting frequency-dependent characteristics. They don’t simply sum to 100%)

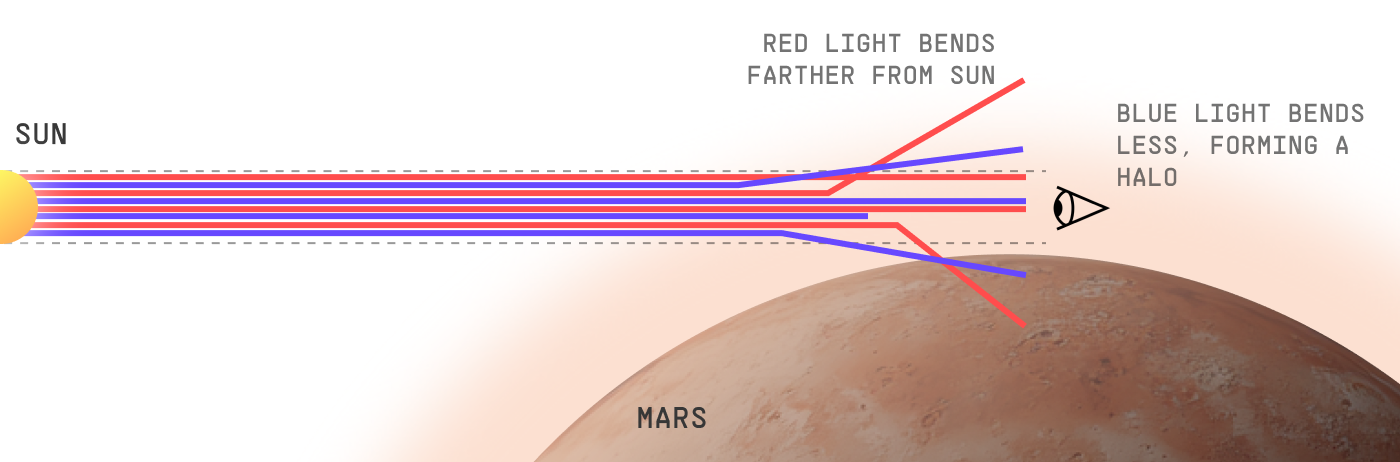

Small atmospheric particles, like dust and smog, are equal-opportunity scatterers. The absolute probability they’ll scatter a photon does not change significantly with the photon’s wavelength. However, different-frequency photons can be more or less likely to scatter in different directions.

For our purposes, it suffices to know that Martian dust – like many atmospheric particles of similar size – generally scatters blue light closer to the direction it was already going. Red light has a higher probability of deflecting at a greater angle.

When molecules deflect photons only a tiny angle, it’s called “forward scattering”. Forward scattering is the most pronounced for larger particles, like dust or smog aerosols. It’s actually so strong on Mars that even at midday, red light doesn’t fill the sky evenly – the sky opposite the sun is noticeably darker!

But blue’s tendency to forward-scatter more directly against Martian dust means the Martian sunset has a blue halo.

Building a model

At the beginning of this article, I said being able to predict something is a good measure of how well you understand it. Let’s do that now. Let’s build a model for predicting the sky color on new planets/moons, or during different scenarios on our own planet.

(Not the most practical thing, but a good nerdsnipe 🙂)

Here are the three general rules of thumb we’ve already talked about.

Small gas molecules = blue/green atmosphere

Atmospheric gases tend to be much, much smaller than the wavelengths of visible light. In these cases, they tend to preferentially scatter blue/violet/UV. This means that gaseous atmospheres are usually blue or blue-green.

Patrick Irwin, University of Oxford.

Patrick Irwin, University of Oxford.

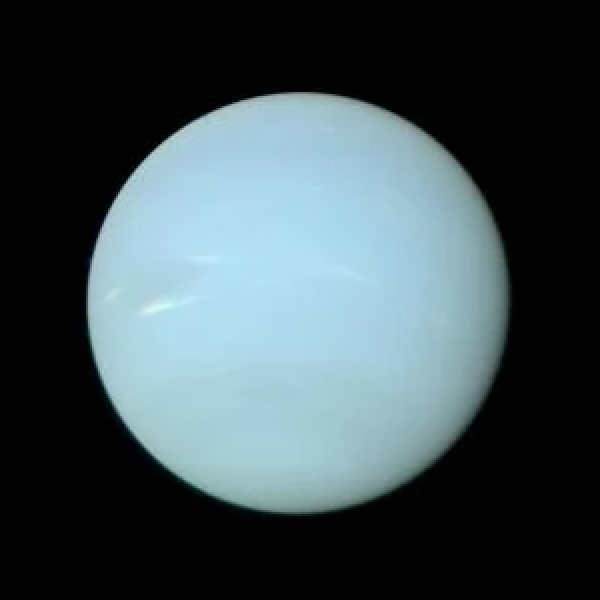

This is pleasingly true for Earth, Uranus, and Neptune[4].

You may recall Neptune as looking like a much darker, richer blue. However, more recent analysis by Patrick Irwin shows the true color is very likely closer to what’s shown here.

It's also worth noting that Neptune and Uranus's blue color is made noticeably richer by the red-absorbing methane in their atmospheres.

Dust or haze = red/orange/yellow atmospheres

When visible light hits particles that are in the ballpark of its own wavelength, things get more complicated and can differ on a case-by-case basis.

These particles are typically either:

- Dust: solid particles kicked up by mechanical means (wind, volcanos, meteorites)

- Haze: solid particles formed by chemical reactions in the atmosphere

Dust and haze generally makes atmospheres appear warmer colors – e.g. red, orange, yellow.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/ASU/MSSS

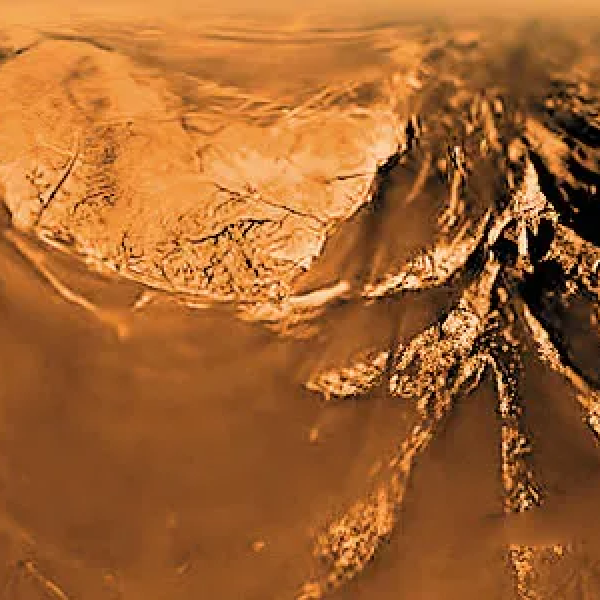

ESA/NASA/JPL/University Of Arizona

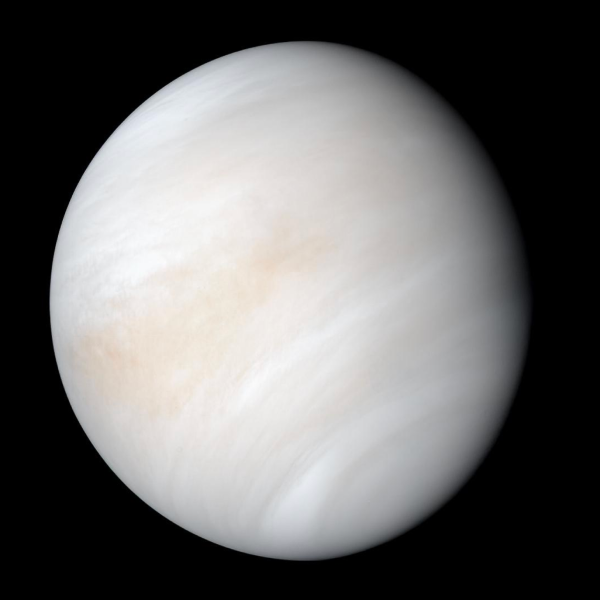

Russian Academy of Science, processing by Don Mitchell

All three significantly dusty/hazy atmospheres in our solar system hold to this rule!

- Mars’s sky is red due to iron oxide-rich dust

- Titan’s sky is orange due to a haze of tholins (organic molecules)

- Venus’s sky is yellow to a haze of sulfurous compounds

Clouds = white/gray

When visible light hits clouds of droplets (or ice crystals) that are much bigger than light’s wavelength, the droplets act akin to a vast army of floating prisms, sending out all colors in all directions.

Consequently, clouds tend to appear white, gray, or desaturated hues.

(Provided the cloud is hit by white light from the sun, that is. If a cloud is below a thick haze or doesn’t receive all wavelengths, neither can it reflect all wavelengths)

NASA

NASA/JPL-Caltech

NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS

Putting it all together

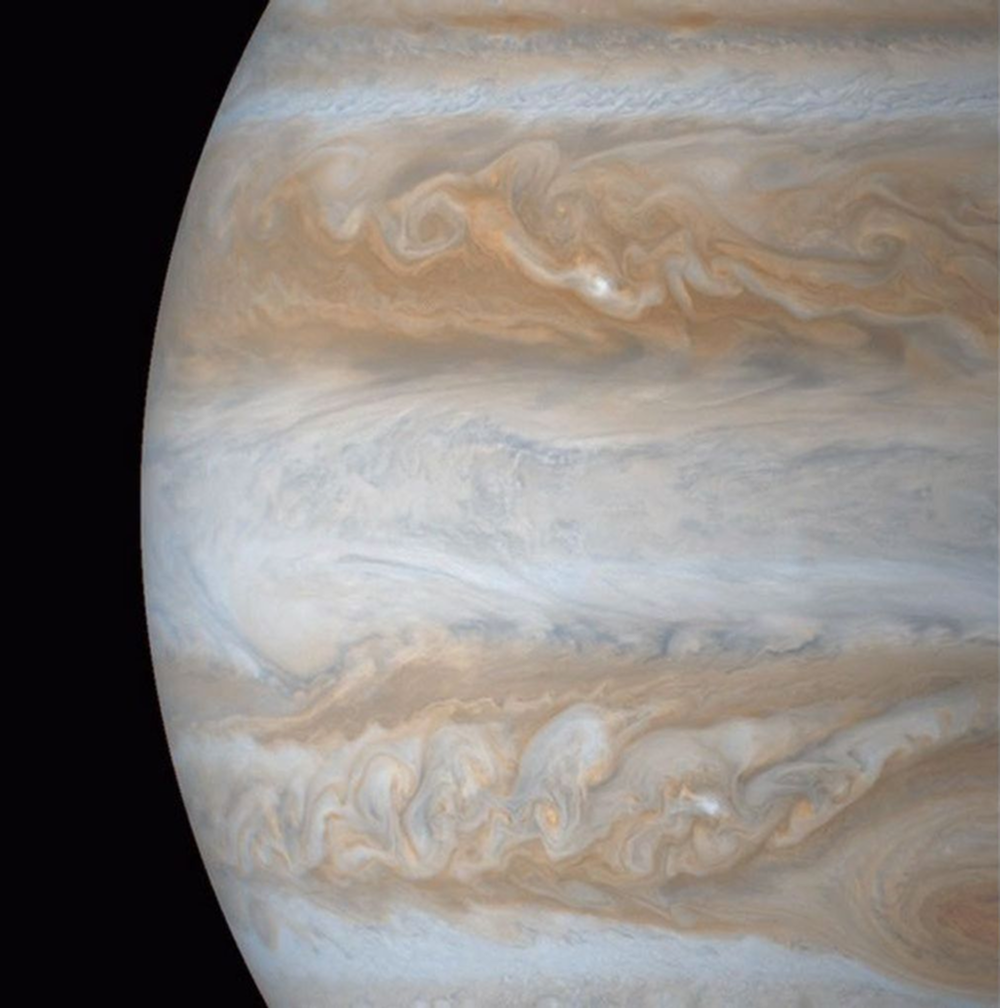

The largest and most complex atmosphere in our solar system is Jupiter. But we know enough to start making some smart guesses about it!

QUIZ: looking at this picture, what can you say about Jupiter’s atmosphere? Answers below the image, so take a guess before scrolling 😉

NASA/JPL/University of Arizona

Here’s a comparison of how a basic guess – informed by our simplistic model – compares to scientific consensus.

| Color | Our guess | Scientific consensus |

|---|---|---|

| Red | Haze (couldn’t be dust; a liquid core makes that impossible) | A haze of unknown composition |

| White | Clouds, probably of ice because of coldness | Clouds of ammonia ice |

| Slate (dark blue-gray) | Small atmospheric molecules. But potentially a chemically odd haze, if something absorbed the visible spectrum pretty strongly? | Hydrogen and helium – i.e. small gaseous molecules that scatter blue/violet[5] |

The Galileo probe that descended into Jupiter entered one of these spots. It’s most surprising finding was how dry Jupiter’s atmosphere seemed to be. But knowing it fell between where the clouds were, this makes total sense. Instead of ice crystals, it found hydrogen and helium.

We didn’t do too bad, huh? A few key ideas explain a lot of sky color!

I’ll wrap up by connecting what we’ve covered to the larger picture of scattering.

Scattering: the bigger picture

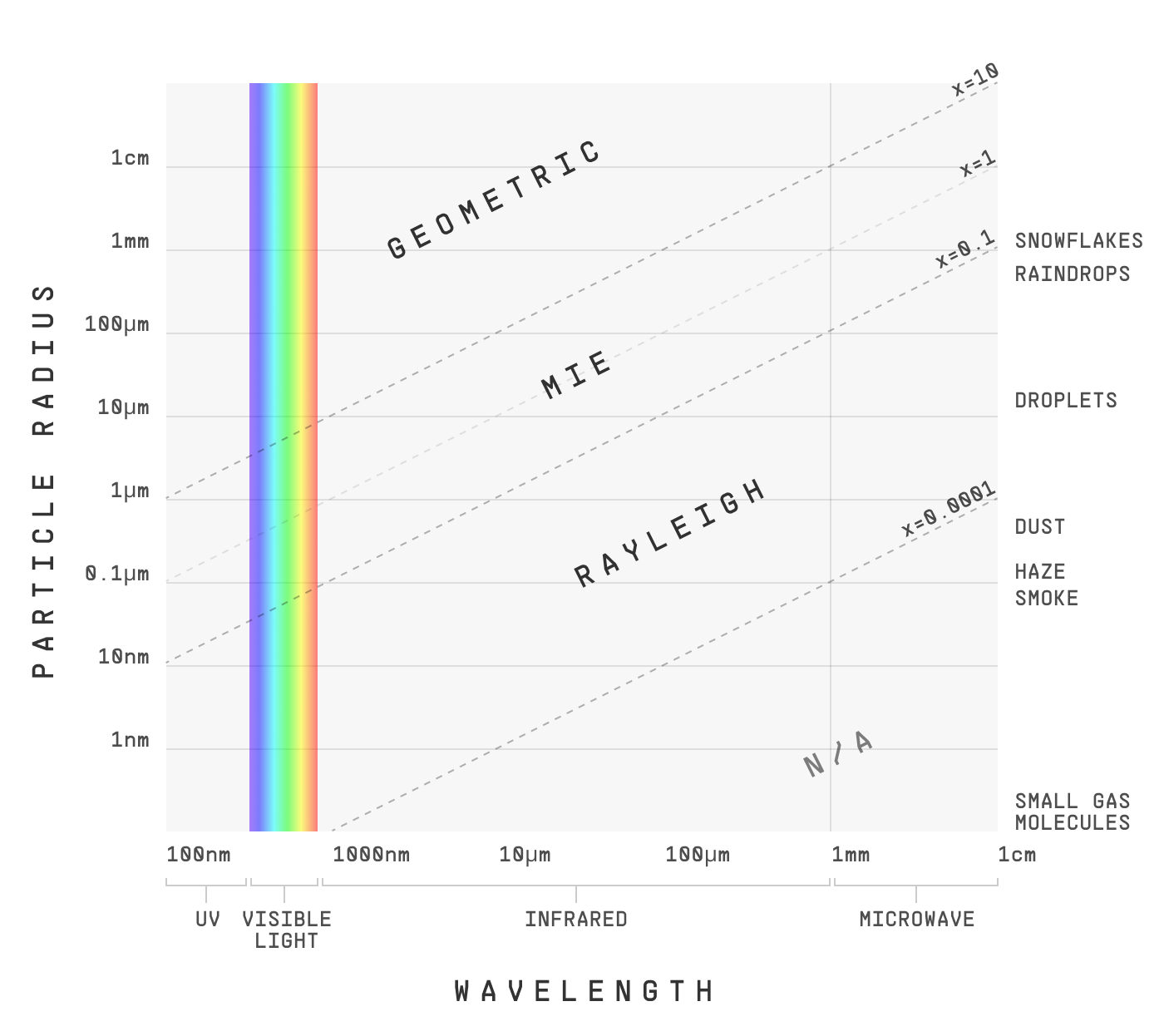

Scientists have official names for the three types of scattering we’ve talked about. I’d be remiss not to at least mention them:

- Rayleigh scattering: when the wavelength of light is much larger than the particle (e.g. visible light and tiny gas molecules)

- Mie scattering: when the wavelength of light is the same order of magnitude as the particle (e.g. visible light and dust/haze)

- Geometric scattering: when the wavelength of light is much smaller than the particle (e.g. visible light and droplets or ice crystals)

And yes, somewhat strangely, it’s not the absolute particle size that determines how it scatters light. It’s the relative size of the particle to the wavelength of light.

| Property | Rayleigh Scattering | Mie Scattering | Geometric Scattering |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relative particle size | ~10-10,000x smaller than wavelength | Within ~0.1-10x of the wavelength size | >10x the wavelength size |

| Particle example (for visible light) |

Gas molecules | Dust, haze | Droplets, ice crystals |

| Color effect (in visible spectrum) |

Blue, violet | Commonly warm, but varies case by case | Whites, neutral |

| Wavelength dependence | Highly favors short wavelengths | Irregular or none | Negligible |

| Directionality of scattering | Nearly symmetric | Strongly forward scattering, especially as relative particle size increases | All directions |

| Role of absorption | Depends on wavelength, but negligible for visible spectrum | Often major, but varies case by case | Negligible |

This table implies that if you take a particle and shine longer and longer wavelength light on it, it’ll go from one domain to the next. And that’s true!

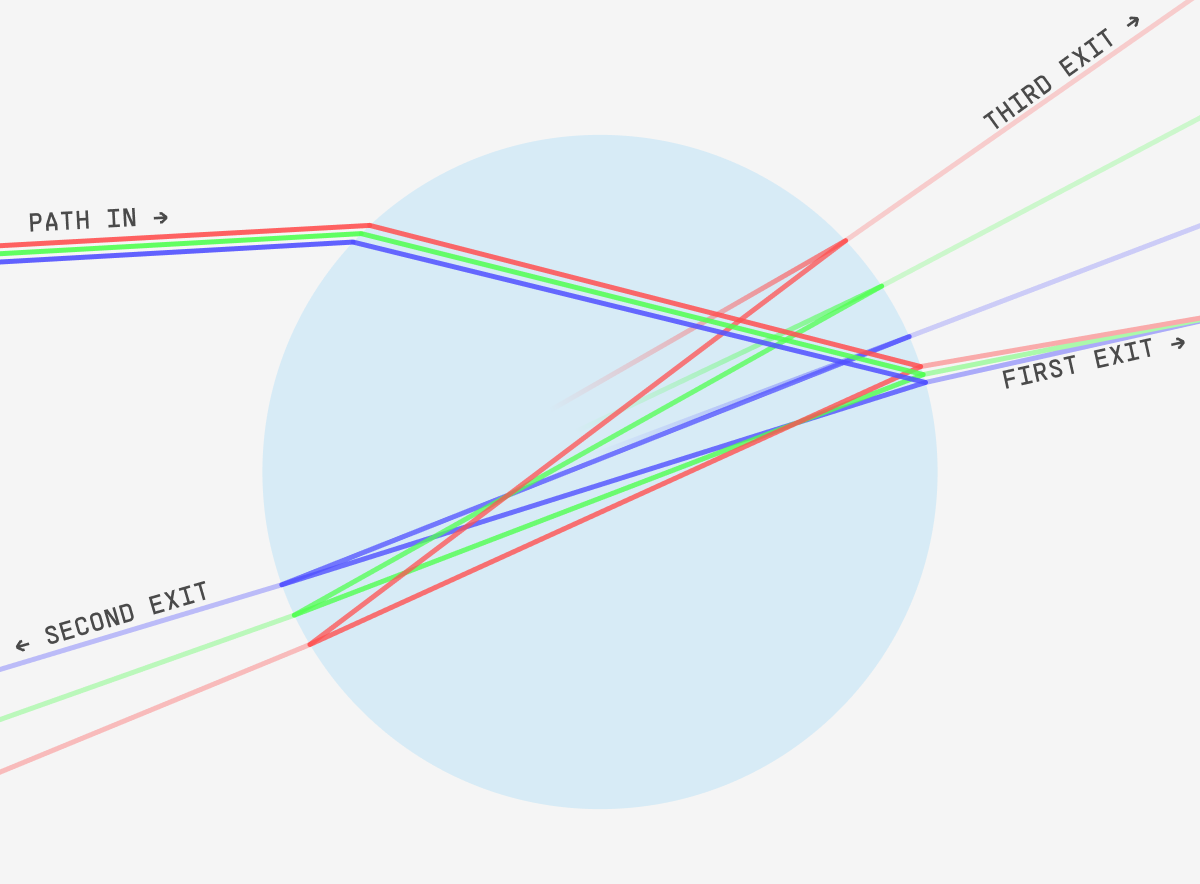

The full picture looks a bit like this:

This has some exciting implications. Say you have a thick smoke, opaque to the naked eye. Why not just look at the infrared range instead? If you use a long enough wavelength, smoke particles will be in the Rayleigh domain – where, of course, shorter wavelengths scatter much more than longer. So if we use a suitably long wavelength of infrared… the opaque becomes transparent.

That’s what firefighters do, anyhow!

Smoke particles are in the Mie domain for visual light. Thick smoke can absorb enough light to become opaque. But in the infrared range, it’s the Rayleigh domain. There, long wavelengths mean less scattering. Less scattering means more transparency. And thus, infrared can see through smoke.

I’m getting off-topic. I can’t help it. So let’s call it here. As you can see, what we’ve covered above is but a tiny droplet in a vast cloud.

But at least you know why the sky’s blue.

Further Resources

- NASA’s sunset simulator. You know who really wants to know what color the sky is on other planets? NASA. They’ve built an incredibly powerful app for modeling atmospheres and radiation, and here they use it to crank out a few beautiful visuals of our solar system’s best sunsets.

- Blue Moons and Martian Sunsets. The mechanics of Mars’s blue sunsets are still somewhat debated. The authors of this article make a convincing model based on the assumptions I worked with above.

Thank you to Dr. Patrick Irwin, Dr. Craig Bohren, and Matt Favero for corrections and feedback. LLMs were consulted in the research of this article, but any hallucinations are my own. I welcome further feedback.

Well ackshually… 🧐

These sidenotes are optional to read, but I’ll use them for giving the fuller technical details when I’ve abbreviated things in the main body of the text.

In this case, the color you see is determined by the wavelengths of light entering your eye since (1) you may be seeing a pure frequency, but in almost all cases, (2) you’re seeing many frequencies, which your brain interprets as a single color.

For instance, the sensation of turquoise at a specific point can be caused by (a) photons of wavelength 500nm emanating from that point, (b) a specific combo of photons of wavelengths 470nm and 540nm, or (c) (mostly realistically) photons of a huge number of wavelengths, probably peaking somewhere around 500nm.

In the text, I am a bit fast and loose with the difference. ↩︎

“Scattering” is the scientific term of art for molecules deflecting photons. Linguistically, it’s used somewhat inconsistently. You’ll hear both “blue light scatters more” (the subject is the light) and “atmospheric molecules scatter blue light more” (the subject is the molecule). In any case, they means the same thing 🤷♂️ ↩︎

A small cloud may be a quadrillion droplets. ↩︎

You may recall Neptune as looking like a much darker, richer blue. However, more recent analysis by Patrick Irwin shows the true color is very likely closer to what’s shown here. It's also worth noting that Neptune and Uranus's blue color is made noticeably richer by the red-absorbing methane in their atmospheres. ↩︎

The Galileo probe that descended into Jupiter entered one of these spots. It’s most surprising finding was how dry Jupiter’s atmosphere seemed to be. But knowing it fell between where the clouds were, this makes total sense. Instead of ice crystals, it found hydrogen and helium. ↩︎