15 years of FP64 segmentation, and why the Blackwell Ultra breaks the pattern

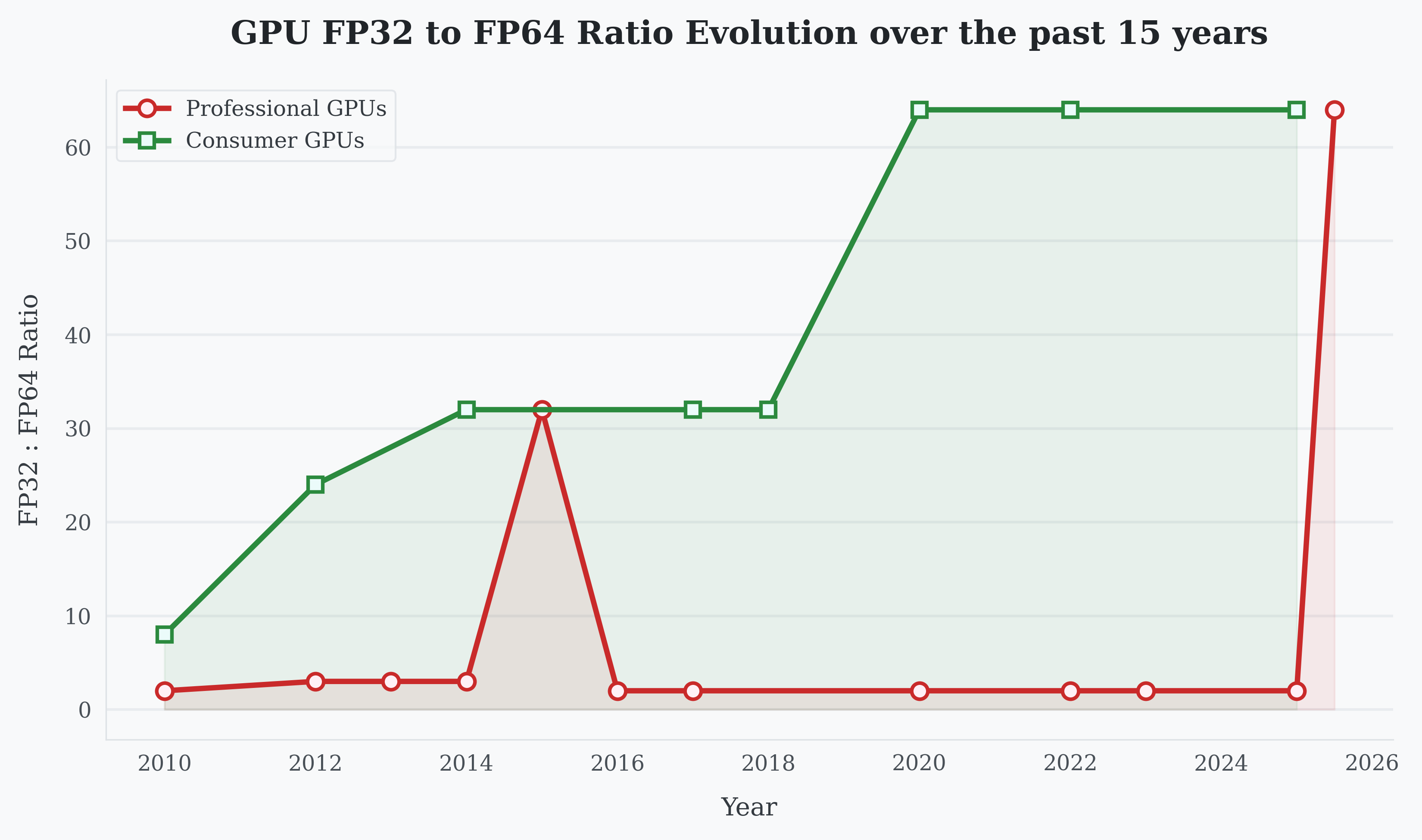

Buy an RTX 5090, the fastest consumer GPU money can buy, and you get 104.8 TFLOPS of FP32 compute. Ask it to do double-precision math and you get 1.64 TFLOPS. That 64:1 gap is not a technology limitation. For fifteen years, the FP64:FP32 ratio has been slowly getting wider on consumer GPUs, widening the divide between consumer and enterprise silicon. Now the AI boom is quietly dismantling that logic.

The Evolution of FP64 on Nvidia GPUs

The FP64:FP32 ratio on Nvidia consumer GPUs has degraded consistently since the Fermi architecture debuted in 2010. On Fermi, the GF100 die shipped to both GeForce and Tesla lines; the hardware supported 1:2 FP64:FP32, but GeForce cards were driver-capped to 1:8.1

Over time, Nvidia moved away from “artificially” lowering FP64 performance on consumer GPUs. Instead, the architectural split became structural; the hardware itself is fundamentally different across product tiers. While datacenter GPUs have consistently kept a 1:2 or 1:3 FP64:FP32 performance (until the recent AI boom, more on that later), the performance ratio on consumer GPUs has consistently gotten worse. From 1:8 on the Fermi architecture in 2010 to 1:24 on Kepler in 2012 to 1:32 in 2014 to our final 1:64 ratio on Ampere in 2020.

This effectively also means that over 15 years, from the GTX 480 in 2010 to the RTX 5090 in 2025 the FP64 performance on consumer GPUs only increased 9.65x from 0.17 TFLOPS to 1.64 TFLOPS, while in the same time range the FP32 performance improved a whopping 77.63x from 1.35 TFLOP to 104.8 TFLOP.

Nvidia's Move to Segment the Market

So why has FP64 performance on consumer GPUs progressively gotten weaker (in relation to FP32) while it stayed consistently strong on enterprise hardware?

If this were purely a technical or cost constraint, you would expect the gap to be smaller. But since historically, Nvidia has taken deliberate steps to limit double-precision (FP64) throughput on GeForce cards, it makes it hard to argue this is accidental. The much simpler explanation is market segmentation.

Most consumer workloads, such as gaming, 3d rendering, or video editing do not need FP64. High-performance computing on the other hand has long relied on double precision (FP64). Fields such as computational fluid dynamics, climate modeling, quantitative finance, and computational chemistry depend on numerical stability and precision that single precision (FP32) cannot always provide. So FP64 becomes a very convenient lever: weaken it on consumer GPUs, preserve it on enterprise versions, and you get a clean dividing line between markets. Nvidia has been fairly open about this. In the consumer Ampere GA102 whitepaper, they note "The small number of FP64 hardware units are included to ensure any programs with FP64 code operate correctly.".3

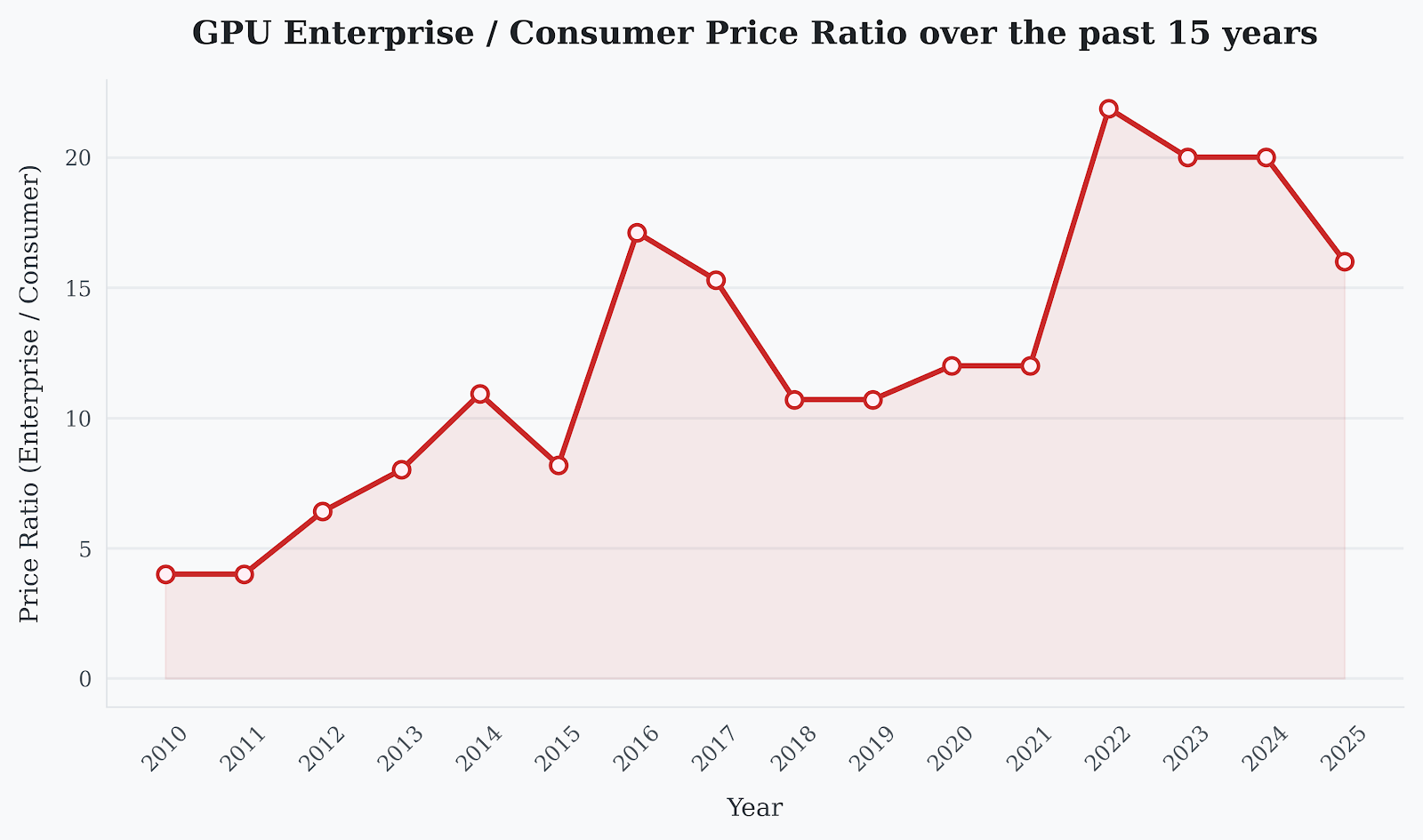

And the segmentation worked. Over time, the price gap between consumer GPUs and datacenter GPUs widened from roughly 5x around 2010 to over 20x by 2022. Enterprise cards commanded massive premiums, justified in part by their strong FP64 performance (among other features like ECC memory, NVLink, support contracts, and so on). From a business standpoint, the elegance is obvious: closely related silicon sold into two markets at vastly different margins, with FP64 throughput serving as a clear dividing line.

Modern AI training largely does not depend on FP64 though. FP32 works fine, and on the contrary lower precisions (FP16, BF16, FP8, even FP4) are often preferred. Suddenly, consumer GPUs looked surprisingly capable for serious compute workloads. Researchers, startups, and hobbyists could train meaningful models without the purchase of an expensive Tesla or A100. In response, Nvidia updated its GeForce End User License Agreement (EULA) in 2017 to prohibit use of consumer GPUs in datacenters, in a divisive move. In what was (to my knowledge) an unprecedented shift, implicit technical segmentation was replaced by explicit contractual restrictions.5

How FP64 Emulation and AI Is Changing the Game

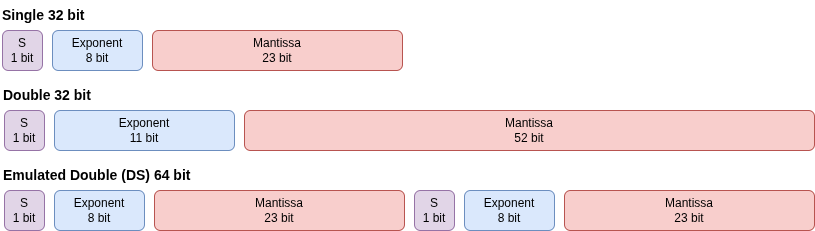

What if you have an old RTX 4090 lying around at home and, for some reason, you need the precision of FP64 but the built-in FP64 capabilities are not sufficient? Aside from the obvious answer of purchasing enterprise GPU power, FP64 emulation using FP32 floats can be an answer. This concept dates back to 1971, when T. J. Dekker described double-float arithmetic.6

The simple idea is to split a 64-bit floating point number into two 32-bit floating point numbers: A = a_hi + a_lo. The a_hi term carries the most significant bits, while a_lo captures the rounding error. Andrew Thall proposed a bunch of common algorithms for emulated FP64s (summation, multiplication, etc.) back in 2007 when GPUs did not have FP64 capabilities.7 You lose 5 bits of precision as your effective mantissa is only 48 bits (twice the FP32 effective mantissa) and not the FP64 53 bits of precision. If a modest reduction in numerical precision is acceptable, you may be able to achieve substantially higher throughput by using emulated double-precision computation. This can be advantageous given the steep FP64-to-FP32 performance disparity, even after accounting for the overhead introduced by emulation.

A newer scheme that preserves full 64-bit precision but only works for matrix multiplication is the Ozaki scheme.8 This scheme exploits the speedup of tensor cores (specialized hardware for matrix multiply-accumulate (MMA) operations) and the distributive property of matrix multiplication.9 The Ozaki scheme splits FP64 numbers into, for example, FP8 numbers:

A = A1 + A2 + A3 + ... + Ak

where A1 contains the most significant bits and A2 contains the next slice of bits and so on. We then calculate:

Ai Bi

for each Ai and Bi. All the results are summed back up in 64-bit precision:

AB = Σ Ai Bi

The Ozaki scheme is gaining increasing traction thanks to the abundance of extremely fast FP8 and FP4 tensor cores being deployed for AI workloads. NVIDIA added support for the Ozaki scheme in cuBLAS in October 2025 and plans to continue developing it.10

From a GPU manufacturer's perspective, this direction is logical. The majority of enterprise GPU revenue now comes from AI applications; market segmentation based on FP64 performance makes no more sense. Enhancing FP64 emulation through low-precision tensor cores allows a reduction in the relative allocation of dedicated FP64 units in enterprise GPUs while expanding FP8 and FP4 compute resources that directly benefit AI workloads.

The latest generation of NVIDIA enterprise GPUs, the B300 based on the Blackwell Ultra architecture, represents a decisive shift toward low precision. FP64 performance has been significantly reduced in favor of more NVFP4 tensor cores, with the FP64:FP32 ratio dropping from 1:2 to 1:64.11 In absolute terms, peak FP64 performance declines from 37 TFLOPS on the B200 to 1.2 TFLOPS on the B300. Paradoxically, instead of consumer hardware catching up to enterprise-class capabilities, enterprise hardware is now embracing constraints traditionally associated with consumer GPUs.

Does this signal a gradual replacement of physical FP64 units through emulation? Not necessarily. According to NVIDIA, the company is not abandoning 64-bit computing and plans future improvements to FP64 capabilities.11 Nonetheless, FP64 emulation is here to stay, exploiting the abundance of low-precision tensor cores to supplement hardware FP64 for HPC workloads.

But the segmentation logic hasn't disappeared; it may simply be migrating. The RTX 5090 delivers a 1:1 FP16:FP32 ratio, while the B200 sits at 16:1. For fifteen years, FP64 was the dividing line between consumer and enterprise silicon. The next divide may already be taking shape in low-precision floating point.

- AnandTech: GTX 480/470 FP64 ratio discussion (archived). https://web.archive.org/web/20100402215300/http://www.anandtech.com/show/2977/nvidia-s-geforce-gtx-480-and-gtx-470-6-months-late-was-it-worth-the-wait-/6 ↩

- Google Sheets: numbers used for the computations. https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1NHHlgVytLx43DGzP8HlPeOCs7HKPElgpSO__9j6oMFo/edit?usp=sharing ↩ ↩

- NVIDIA Ampere GA102 GPU Architecture Whitepaper (PDF). https://www.nvidia.com/content/PDF/nvidia-ampere-ga-102-gpu-architecture-whitepaper-v2.pdf ↩

- Alibaba Product Insights: A100 vs RTX 3090—Is the A100 Really Worth the Hype and Extra for Deep Learning? https://www.alibaba.com/product-insights/a100-vs-rtx-3090-is-the-a100-really-worth-the-hype-and-extra-for-deep-learning.html ↩

- Wccftech on 2017 GeForce EULA datacenter restriction. https://wccftech.com/nvidia-geforce-eula-prohibits-datacenter-blockchain-allowed/ ↩

- T. J. Dekker (1971), double-float arithmetic. https://csclub.uwaterloo.ca/~pbarfuss/dekker1971.pdf ↩

- Andrew Thall (2007), Extended-Precision Floating-Point Numbers for GPU Computation. https://andrewthall.org/papers/df64_qf128.pdf ↩

- Ozaki et al. (2011), Error-Free Transformations for Matrix Multiplication. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11075-011-9478-1 ↩

- NVIDIA blog: Tensor Cores for Science (ISC 2025). https://developer.nvidia.com/blog/nvidia-top500-supercomputers-isc-2025/#tensor_cores_for_science%C2%A0 ↩

- NVIDIA blog: Unlocking Tensor Core Performance with Floating-Point Emulation in cuBLAS. https://developer.nvidia.com/blog/unlocking-tensor-core-performance-with-floating-point-emulation-in-cublas ↩

- HPCwire: NVIDIA says it's not abandoning 64-bit computing (Dec 9, 2025). https://www.hpcwire.com/2025/12/09/nvidia-says-its-not-abandoning-64-bit-computing/ ↩