'My farmer dad was part of Churchill's Secret Army'

Katy Prickettat Parham Airfield Museum

Katy Prickett/BBC

Katy Prickett/BBC

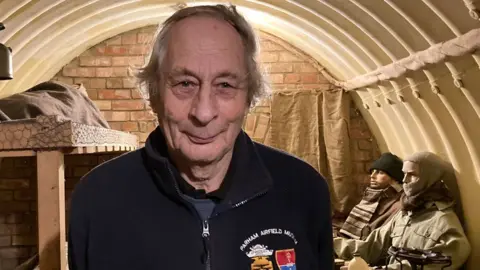

Peter Kindred grew up in a farmhouse stuffed with World War Two arms and explosives.

His father's Home Guard uniform was hanging in a wardrobe upstairs; the munitions must relate to his time in "Dad's Army", he thought.

It turned out Percy Kindred was in a resistance organisation which would have faced almost certain death in the event of an expected German invasion of Britain.

The family began to realise Percy's story was something unusual, when his grand-daughter started a school project on his wartime experiences.

"He wouldn't give much away in those days, just the bare bones," said Peter, 80, from Stratford St Andrew in Suffolk.

Percy was wary about saying too much because in 1940 he had signed the Official Secrets Act, which bound him to silence for life.

With his brother Herman, he spent the war preparing for an invasion in the organisation later nicknamed "Churchill's Secret Army".

British Resistance Museum

British Resistance Museum

The Kindred brothers had been recruited into the Stratford St Andrew operational patrol — a unit of about eight men based in the village which is on the A12 about five miles inland from the coastal town of Aldeburgh.

- WW2 resistance units inspire new play

- The ongoing problem of WW2 unexploded bombs on Suffolk's shores

- Britain's WW2 secret army uncovered

They were "stay-behinds", expected to remain behind enemy lines after a German invasion, carrying on with their usual work during the day, and wreaking havoc from their operating bases (OB) during the night.

An OB was a secret underground bunker, with a concealed entrance, and supplied with beds, tables, and food and ammunition for a couple of weeks.

As farmers, the young men were in a reserved occupation, exempt from military service.

British Resistance Museum

British Resistance Museum

"Their role was to interdict supply lines doing what the resistance did — blowing up railway lines and attacking airfields," said British Resistance Museum curator Chris Pratt.

"You're either going to get killed in action or, if you're captured, you're going to get shot - it would very much have been a suicide mission."

Countrymen like Percy and Herman were ideal recruits — able to shoot game for the pot to supplement their supplies.

They "very much liked to use their .22 rifle to go and get some pheasants from the aristocracy next door [the neighbouring farm] which they could cook up on the stove in the base", said Mr Kindred.

In 1940, patrols were recruited all down the coasts of east Scotland, eastern and southern England and southern Wales.

Why plan a resistance?

Getty

Getty

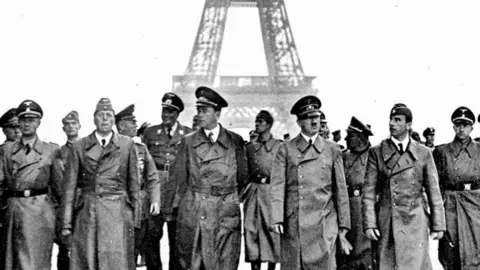

Most of mainland Europe had been over-run by Nazi Germany and on 16 July, Adolf Hitler announced plans to invade and if necessary, occupy Britain.

Even if this were a bluff, preparations were made.

By the end of July, 1.5 million men had joined the Home Guard, and a series of barriers or stop-lines, were hastily constructed, sealing off beaches and points further inland, designed to bog down enemy troops.

Meanwhile, behind the scenes, Britain became the only European country to set up a resistance organisation ahead of invasion.

British Resistance Museum

British Resistance Museum

Maj Gen Colin Gubbins, the Auxilliary Units' first commanding officer, was given approval by the War Cabinet to recruit locals who, in his words, "could appear from nowhere, hit hard and then melt away as mysteriously as they came".

An expert in irregular warfare, his model was in part inspired by his service in Ireland between 1919 to 1922 [the Irish War of Independence].

"Gubbins was aware of the way the cellular structure of the IRA [Irish Republican Army] worked, keeping cells separate from each other and not aware of who was involved three or four miles down the road," said Mr Pratt.

"It isn't a question of taking the battle to the enemy — it's trying to reduce the effect of the invasion."

Katy Prickett/BBC

Katy Prickett/BBC

The museum is based at Parham Airfield Museum, near Stratford St Andrew, and it is the only one in the UK to tell the stories of the men and women who served in these Auxiliary Units.

"The men were mainly involved in the operational patrols," explained Mr Pratt.

"The special duties section was involved in intelligence gathering — vicars, doctors, district nurses, midwives — people who, come the invasion, were still needing to get out and do their day job."

Every recruit in every capacity had to sign the Official Secrets Act.

Guerrilla training

Coleshill Auxiliary Research Team

Coleshill Auxiliary Research Team

About 3,500 men were trained in guerrilla tactics at the Auxiliary Unit's HQ at Coleshill House, a mansion about 10 miles from Swindon.

There was also training on the ground, several times a week, and many would later be recruited by the SAS.

Mr Pratt said: "Each county had a couple of sections of six or seven men, recruited from the regular Army, called the Scout Sections.

"They went into the countryside to train these newly-recruited guerrillas, mainly in sabotage and demolition and of course in close-quarter combat — you need to be able to silence a sentry on an airfield without him waking his comrades."

It would be up to the Army, supported by the Home Guard, to organise any counter attacks.

Intelligence gathering

British Resistance Museum

British Resistance Museum

Once the invasion troops had arrived, the men and women of the special duties section would have come into their own.

Their training involved learning how to identify German units, tanks, planes and other vehicles, gathering useful information for the defending forces.

One of their couriers was school girl Jill Monk, recruited by her father, a doctor in Norfolk.

"She was always riding her horse around the area, so his theory being that come invasion, she would be a perfect courier for relaying messages through to their radio network," said Mr Pratt.

Jill was aged about 12 or 13 at the time.

Recruited in Harrods

British Resistance Museum

British Resistance Museum

Meanwhile a network of ATS [Auxiliary Territorial Service] wireless operators had been readied by senior commander Beatrice Temple.

Mr Pratt said: "She interviewed all the recruits, often in the lounge of the London department store, Harrods.

"They were sent to underground bases, expected to relay the information gathered by the informants to the Army."

Yvonne Alston worked for a big special duty section unit at the Henniker estate at Thornham Magna, in Suffolk, while Thea Ward was another ATS radio operator based at Great Yeldham in north Essex.

Her husband Ken Ward helped design the TRD, a special radio which it was believed could not be intercepted by the enemy.

Sworn to secrecy

British Resistance Museum

British Resistance Museum

As the risk of invasion receded, the Auxiliary Units were stood down at the end of 1944.

The Stratford St Andrew munitions remained in the OB until it became too damp, when Percy brought them to his farmhouse.

"Because they were so top secret, no-one was there to take back all their ammo, take back their guns," explained Mr Kindred.

Katy Prickett/BBC

Katy Prickett/BBC

Such was the secrecy, the family was unaware until years after his death that their cousin Charles Kindred, on a neighbouring farm, had also been in the Auxiliary Units.

This changed after special branch superintendent John Warricker retired and moved to Great Glenham in 1992.

"Herman Kindred told him, 'I have a good story to tell about my wartime activities, but I can't because I've signed the Official Secrets Act'," said Mr Pratt.

"He got someone from the Cabinet Office to speak to Herman and say enough time had passed."

Mr Warricker is regarded as "the oracle of the Auxiliary Units" and has written books on the subject, added Mr Pratt.

The museum was opened in 1997 and now holds a huge variety of artefacts donated by former Auxiliaries - as well as a replica of the Stratford St Andrew OB.