You Don't Understand How Bad It Is Here | On trying to capture the staggering cruelty of Israel's occupation of the West Bank

In the middle of this nightmare in Gaza, I traveled to the West Bank to bear witness to Palestinian life under the occupation (I am a Jewish American guy who lives in Brooklyn, for those who don’t know)—I guess I got tired of being told, “You don’t understand.” The plan had been to send out dispatches along the way (as I did from East Africa and across America), but I encountered a few obstacles that forced me to abandon this plan somewhere in the Jordan River Valley where it was presumably trampled by settlers.

First, there is the sheer volume of inputs. Let me show you what I mean. On my first day in Hebron, a local journalist and human rights activist named Hisham Sharabati took me into the Old City. He told me the story of being shot by an Israeli sniper while reporting on the aftermath of the 1994 Cave of the Patriarchs mosque massacre (an act of pure terrorism that Israel’s National Security Minister Itamar Ben-Gvir has long celebrated; Ben-Gvir, a Hebron resident himself, is now arming the violent local settlers), but he was interrupted by a text and then a phone call from the IDF accusing him of participating in a Hamas rally, asking if he was a member of ISIS (??), and finally warning him that he was being watched—punishment for future indiscretions would be severe. As he took the call, I watched the military checkpoint across the street suddenly close up shop, causing the dispersal of a long line of mothers and children with backpacks who had hoped it would be one of those days when they’d make it to school. When Hisham finished taking the call (which gave him a good laugh—these threats are nothing new), we walked through the Old City market.

Everyone knew Hisham, and they knew a wide-eyed American when they saw one, so they were eager to tell me their stories. A grey-haired peace activist described taking a settler’s stone to the face and being unable to reach the only hospital around that could have saved his eye—such is life when you don’t have the right permit. He popped out his glass eye and offered it to me. He showed me security camera footage of a group of settler children following him home and dumping pig fat in his doorway.

Then a woman came by, exasperated, on her way to see her grandchildren—it was the first time she’d been allowed out of her house in weeks due to some arbitrary curfew (she received no explanation, there is never an explanation). She told me that a soldier shot her son in the leg, and a settler pushed her daughter off a roof. We walked through the market. A man in front of an empty clothing shop—the whole market has been empty since 10/7 when Israel locked most of the gates between each town—pointed to his temple to show me where an IDF bullet entered his 15-year-old son’s skull, lodging itself in his brain, leaving him braindead and paralyzed. This happened roughly 20 years ago, so the son was my age. The shopkeeper was an old man now but would be his son’s caretaker for the rest of his life. We walked by a sweets shop. The owner, a real smiley guy with a bad leg, invited us in for (free) baklava and coffee (it has been very difficult to get anybody in Palestine to accept my money). While we ate, drank, and smoked, he stepped outside to look for more customers. A passing soldier said, “Get inside before I break your other leg.”

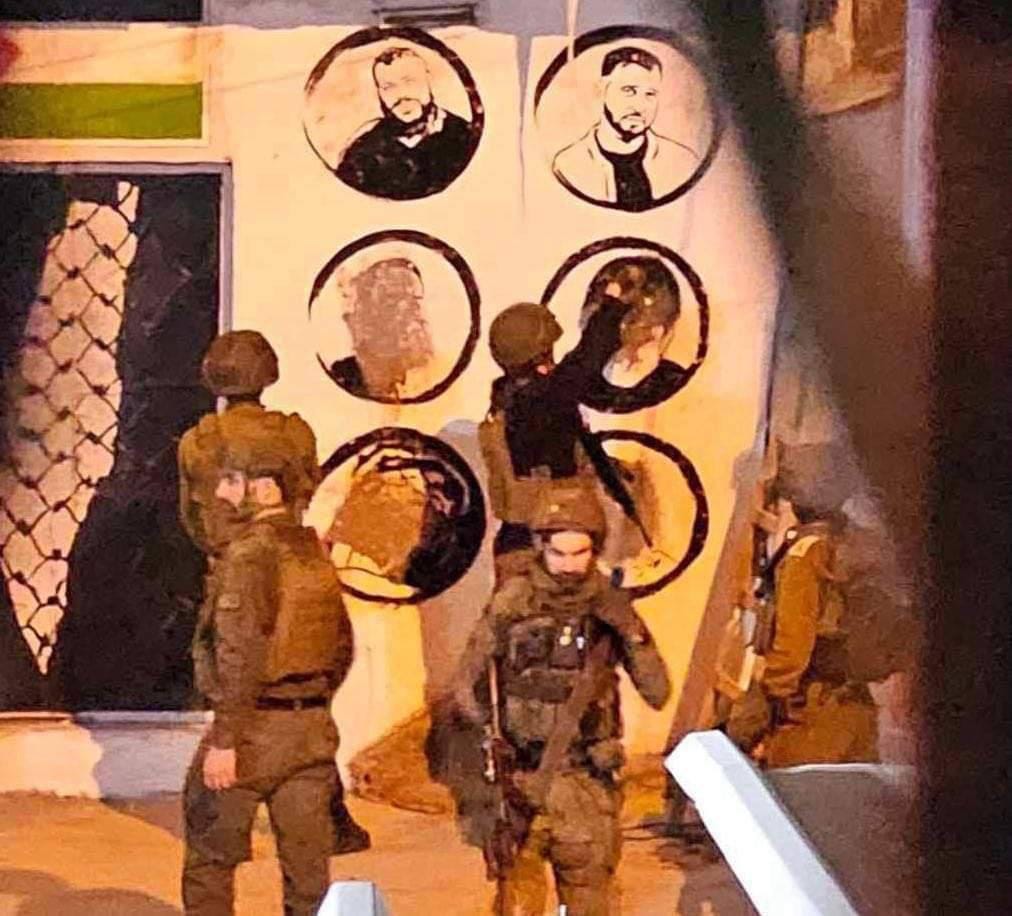

Hisham pointed out the settlement looming above the market behind metal netting, which the locals had installed to prevent settlers from hurling large objects at them. Unfortunately, it has not stopped them from dumping buckets of piss and shit. This, the shopkeepers decided, was better than the alternative of spending their days under the darkness of a protective roof. Nearby, soldiers painted over a refugee camp mural of young men they had recently killed there. When they couldn’t find the artist, they arrested his father and announced he’d be detained until the boy turned himself in (there is a name for this act). He repainted the mural and then received a call from the IDF that said, “Paint over the mural, or we’ll bomb it over your heads.”

All this occurred in my first two hours in Hebron; there are about twelve essays in here, and my notes became increasingly unintelligible as I tried to capture everything and connect all the dots like some manic detective. Still, in my naïveté, I thought I’d be able to synthesize my thoughts every few days and publish something. But the flow of stories was punishing, an acid river with Class-6 rapids and endless interconnected tributaries that could sweep you away or batter you against the rocks. Soon I was drowning in stories and struggling to catch a breath or find a coherent narrative beyond OH MY GOD IT IS SO MUCH WORSE THAN I COULD HAVE IMAGINED.

Note to Readers: I’ve recently taken the plunge into full-time writing and reporting, leaving behind the work that’s paid my bills for the past fifteen years. It’s both exciting and unnerving—journalism isn’t exactly a gold mine these days, and every bit of my reporting, including this trip, is self-funded. I travel with no crew, no security team—just me. But, at the risk of sounding sentimental, I’ve never felt more certain of my purpose. In the end, this feels less like a decision than an inevitability.

To make this sustainable, I’ll be introducing a paywall soon. If you’d like to lock in the lowest rate, I’m offering 20% off this week—$64 for the year, or $6.40 month-to-month.

So there is my next obstacle: the struggle to convey the utter pervasiveness of the occupation’s cruelty. I worry that each story I share undermines this essential aspect by implying a start and stop when the reality is more like a poison coursing through every inch of soil, emitting noxious fumes into schools, museums, hospitals, and homes, causing constant pain and suffering and degradation and, on occasion, a seizure or toxic shock or explosion of blood and death.1 I am convinced that no reasonable person could spend even a week here and come away believing the occupation is morally defensible under any circumstances; the trouble is that most will neither come nor even look too closely.2

Then there is the nature of the Palestinian people: for all their righteous rage, there is impossible joy; for their great depths of despair,3 there is unreasonable hope. There is cultural radiance (I visited museums, art galleries, archaeological wonders), and more than anything, there is warmth, openness, and kindness. They see that I care about them, and so they care about me. There are no issues with where I am from, what my religion is, or what I may have believed six months ago. This phrase may be overused, but there is simply no other way to describe it: I have been treated like family everywhere I’ve gone. And yes, I’ve told most people I’m Jewish.

Another obstacle to writing: my own state. Increasingly I feel the emotional weight of these experiences bearing down on me. I don’t know that I have ever spoken with the family of a murder victim, and in one day in Sabastiya, I found myself in multiple living rooms with weeping mothers, fathers, grandparents, brothers, sisters, and cousins recounting the atrocities committed against their loved ones. I met with a young man who has not recovered from the shock of seeing his best friend’s mutilated body, still smoldering from forty bullets searing the inside of his head, neck, face, chest, and groin. I sat with a boy who was shot in the leg by a soldier one week earlier (his plans to finish high school now put on hold). I met a father of four (including newborn twins) who was shot in the stomach by a settler in October, much of his digestive tract currently taped to the outside of his body, just released from the hospital for a brief rest (and a chance to feel his children’s skin against his own) before he goes back for more surgeries—while we spoke, the settlers returned with IDF soldiers to continue tormenting the village, as they do almost daily. The way that bullets casually fly here and destroy bodies and lives—it’s just staggering. And this is all state-sanctioned. The knowledge that none of these murderous soldiers and settlers will ever be brought to justice casts a sickening pall over these meetings that has left me actually, literally, genuinely speechless on several occasions. I’ve worried about finding my own trouble with the IDF, who has beaten and arrested people across Israel/Palestine for posts they don’t like—in November, an Israeli teacher was held in solitary confinement for sharing a photo of a family killed in Gaza on Facebook. I fear retaliation against the people I’ve reported on; one day after nearly 10,000 people viewed a story I shared about the IDF’s abuse of the Mayor of Sabastiya, his office was raided and the town bombarded with gas bombs.4 Angry, bewildered teenagers pointing large guns at my face, while good for the sinuses, has not been particularly helpful for my mental health.

I’ve had difficult conversations with Palestinians about the most contentious issues surrounding this conflict that I do not even feel I can mention yet (though you can probably guess what they are). I’ve received distressing messages from Jewish people in my life who are very confused by what I am doing, some even accusing me of fueling antisemitism. I am anticipating some painful discussions when I get back home.

Plus, I am very, very tired.

So I’ve concluded that this is not the right time for me to attempt to write about this in any sort of comprehensive way. Here’s what I’m going to do instead:

On an ongoing basis, I’ll write and publish individual stories (and analyses) from the West Bank. As the stories build on one another, hopefully, a clearer picture of the occupation will come into focus and express something fundamental about it that no single story can (and that clarifies Israel’s devastating war on Gaza, which has surprised exactly no one in the West Bank). I’ll also cover my (brief) time in Tel Aviv, which included visiting Hostages Square, attending an anti-Netanyahu rally, and meeting with Israeli activists. I’ll reflect on the American movement to free Palestine, 10/7 through the eyes of Palestinians in the West Bank, the weaponization of Jewish trauma, and more. I’ll publish these as often as I can, though I know better than to promise a particular cadence—unfortunately, I have many other obligations at home.

I’ll continue to share photos, videos, and vignettes on Instagram. If you haven’t already, I’d suggest you follow me (@infinite_jaz) and watch my story highlights about Palestine as a primer.

When the time is right, I’m going to attempt to write a more comprehensive piece that synthesizes all of this and brings something unique into the conversation around the occupation.

Now would be a good time to mention that I also use this newsletter to publish stories, essays, criticism, diatribes, etc., on entirely unrelated topics. I don’t think you’ll mind. Think of them as rainbow sprinkles on a deeply cursed ice cream cone.

One last thing. If you’ve been following me on Instagram, you’ll have seen messages I’ve received from Jews in Israel and the diaspora expressing shock at what’s been hidden from them all their lives, from Palestinians who are closely following this growing interfaith coalition and feeling a semblance of hope, and from others who are as ready as ever to join or continue the fight.

I’ve also shared a few blistering messages I’ve received from people who accuse me of being insufficiently radical, too slow to say “genocide” or grasp the severity of the occupation, too soft on the Israeli Left, and more. I understand this sentiment, I really do—of course, every movement has a shape-shifting opposition that must be contended with, sometimes severely, and there is absolutely a role for resistance and directly confrontational activism.5

But in this newsletter, without leaning away from the most charged-up stretches of America’s favorite third rail, I will do my very best not to alienate anybody who is here with an open mind. I’m a firm believer that the movement to free Palestine will need to convert a lot more people to succeed, and I hope I can play some small role in that.6

For the guiding philosophy of my own activism, I’ll give the last words to the great Palestinian American thinker Edward Said:

“Humanism is the only—I would go so far as saying the final—resistance we have against the inhuman practices and injustices that disfigure human history.”

Thanks all,

Jasper

P.S. Please forward this newsletter to your friends and family and encourage them to sign up. I do this for free—my only goal is to get these stories into the world.

An expert told me to write this:

Pick five people you think would enjoy this newsletter and forward it to them now!