Photo courtesy of Christina Cauterucci

Sign up for the Slatest to get the most insightful analysis, criticism, and advice out there, delivered to your inbox daily.

In January 2024, my wife and I agreed to host a birthday party for our friends’ 2-year-old in our child-free home. The scene was chaotic and joyful, with several young kids running around and scattering croissant crumbs on our sofa while their parents attempted adult conversation over mimosas.

Inevitably, the moment arrived when a child knocked over a drink on our coffee table. It was an old West Elm design with a panel on top and a storage area underneath. The spilled beverage was dripping into the seams, so a crowd of parents rushed to open the table and mop up the liquid pooling within. The first thing they saw when they lifted the panel was a padlocked gun case, helpfully identified by the Smith & Wesson user pamphlet sitting on top, which was now soaked in seltzer.

To be perfectly honest, I’d forgotten I had the gun. Ever since my wife and I moved into a place with more closet space, we rarely used the storage capacity of the coffee table. I was reminded of the firearm in my living room only when someone brought up the topic of recreational gun use—which, in our queer, left-leaning urban social circles, was next to never.

But there I was, facing a crowd of these wide-eyed friends, who were politely dabbing the seltzer off my gun. They were clearly shocked. I choked out some nervous laughter and assured them that the case was locked, the gun inside had another padlock, both keys were hidden, and I had no ammunition in the house. I then explained why I owned the gun, which I will also share with you shortly, and everyone made a few jokes at my expense. They finished cleaning up the mess and got back to watching their kids ruin my house.

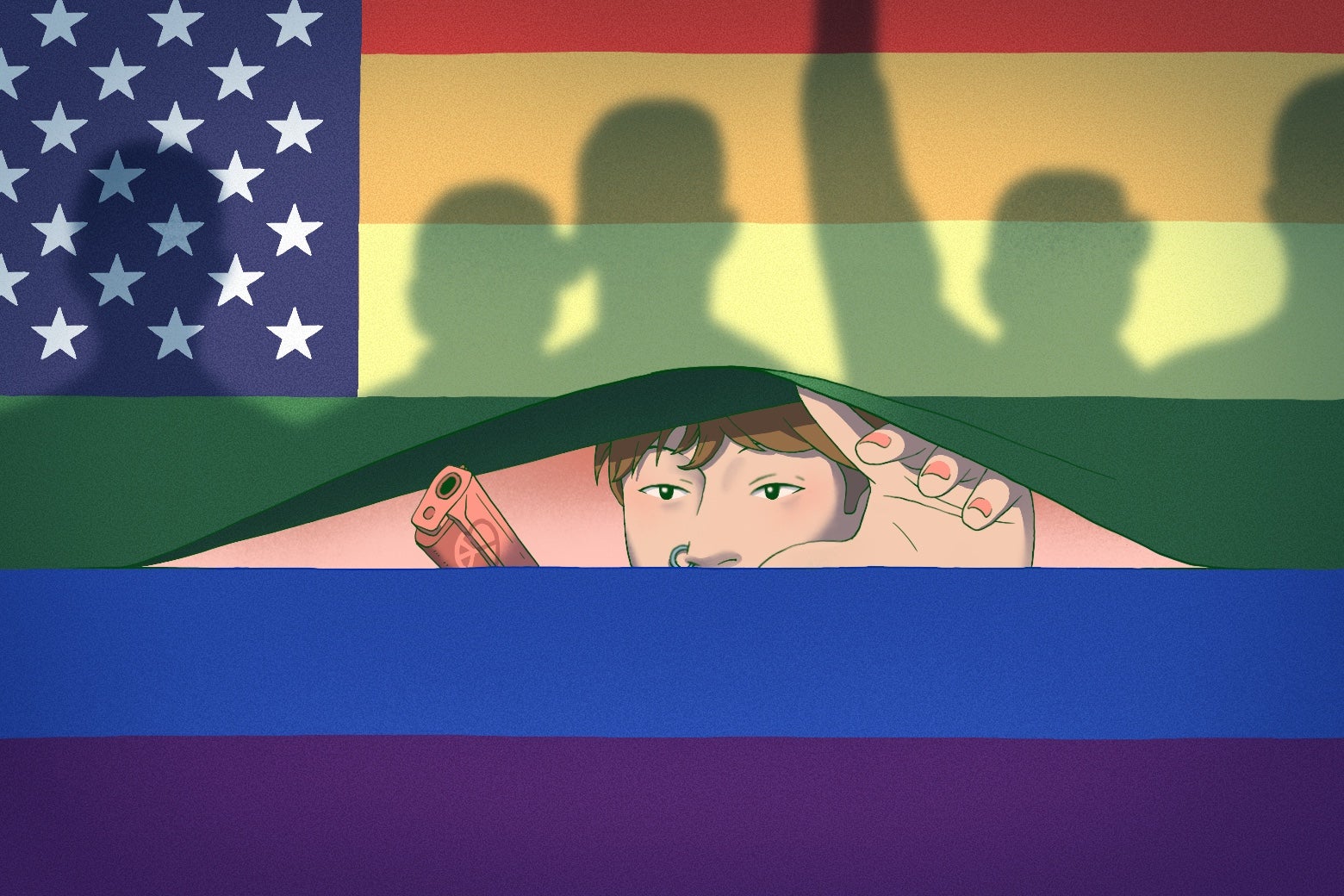

Two years later, as anecdotal reports tell of record numbers of LGBTQ+ people seeking out firearms for self-protection, I think back on that moment as a foreboding encapsulation of the dissonant reality we now inhabit. We film ICE traffic stops outside queer parties before going back inside to dance. We use our gay group chats to plan outings to the bar, and also to share packing lists for go bags. In the morning, we get tipsy at a birthday brunch, letting our children defile our friends’ furniture. In the evening, we research golden-visa options in case the government tells us those children are no longer ours.

In the shadow of Donald Trump’s second term in office, and amid the clear threat and increasing reality of political violence, some queer friends are learning to handle firearms, purchasing new weapons, or researching rifles for defense. Together, we talk through worst-case scenarios that would have seemed fantastical just months ago, imagining ourselves into a million futures that seem possible and unthinkable in equal measure.

Sometimes we don’t even have to imagine. Last month, Renée Nicole Good, a queer mother and poet, was shot to death by an Immigration and Customs Enforcement officer in Minneapolis. Afterward, another agent dismissed her as “that lesbian bitch.” The message was not subtle. Her sexuality was deployed to justify her killing, casting her as a queer agitator who had been put in her place.

If you would have told me 10 years ago that I would one day keep a handgun in my D.C. row house, I would have laughed in your face. If you would have told me five years ago that I might take reasonably seriously the possibility that a real-life scenario might someday incite me to use it, I would have called you insane. But the social and political conditions of American life are changing with alarming speed.

Some queer people have found their views on guns changing too. Unhappily, I’m one of them. My journey over the past 10 years is also the story of many other Americans facing a new reality. I shudder to think where it leads.

In a strange paradox, my lifelong aversion to guns is the very reason why I have one. Nearly a decade ago, an editor suggested a piece wherein a person who believed that all firearms should be melted down and turned into solar panels—i.e., me—would learn to use one, get licensed to carry it, and immerse herself in gun culture to try to understand it from a new perspective.

I gamely accepted the assignment, mostly for novelty’s sake. I gravitate toward new and scary things, and this would require me to do two of them: regularly handle a deadly weapon and fraternize with armed people wearing T-shirts that say “My Pronoun Is Patriot.”

After a four-hour, in-person class on firearm laws and safety, having never shot a handgun in my life, I received a permit that allowed me to carry a concealed firearm in almost every state. (Most states don’t require a permit at all.) Though my permit necessitated no actual shooting experience, I opted to join the other students at a firing range to hone my skills. In the shooting area, our instructor demonstrated how to rack, or “snap” back, the slide of a semiautomatic pistol to load a bullet into the chamber. “Snap with authority,” he said. “Do not snap like you watch Glee.”

The gun was heavier than I had expected. Every part of its preparation took more muscle than I’d anticipated, befitting a complex machine that would enable one of my fingers to send a piece of metal flying 800 mph across the room. My thumbs got torn up pressing the bullets into the rigid spring of the magazine. Feeling a little terrified, I planted my feet and pointed the pistol downrange.

When I pulled the trigger for the first time, it was clear that I had ignited an explosion. The gun jerked back in my hands, emitting a fearsome crack that tore through my ear protection and jolted my nervous system into gear. It took all my wrist strength and yogic belly breaths to keep the thing steady as it lurched in my grip. While I emptied the rest of the magazine into the zombie-clown target at the end of the room, I marveled at how unpleasant the experience was: the whirring ventilation system, the terrible lighting, the acrid smell, the earmuffs that deadened people’s voices but barely masked the gunshots. Every time I squeezed the trigger, I jumped at the blast. I couldn’t believe that people did this for fun.

But in spite of my discomfort—and in spite of (or maybe because of) the nagging awareness that I could easily maim anyone in the room, and vice versa—I felt exhilarated by the power I held in my hands. When the instructor informed me that I had surprisingly accurate aim for a first-timer, the depths of my A-student brain lit up, thrilled by the possibility of excelling at a new task, even this one.

I soon felt myself inhabiting the persona of someone with a riskier life than my own. Thirty years of pop-culture conditioning came bearing down on me, drenching my rented pistol in sex appeal. The act of racking the slide, along with the iconic chick-chick sound it produced, prompted an image of copaganda queen Mariska Hargitay from SVU to float into my mind unbidden. (I assume this is the queer millennial version of the Call of Duty fantasies that draw certain men to stockpile military-grade rifles in their TV rooms and wear tactical gear to Dunkin’ Donuts.) A week later, when I demonstrated my technique to a vehemently anti-gun friend, she conceded, “That’s hot.”

Over the next year, while my editors had me working on other projects, I made occasional progress on my gun research. I went shooting at the National Rifle Association headquarters in the Virginia suburbs. I studied ammunition types and learned that hollow-point bullets are the preferred option for self-defense because they expand and slow down when they hit something. (This makes them less likely to pass through a body and hit an unintended target, and more likely to cause maximum damage to a vital organ.) I was repulsed by the thought of all the scientific expertise that went into these designs, all the physicists and engineers who have lent their skills to the discipline of mutilation.

Around the same time, I could feel the political ground begin to shift. In the fall of 2018, a Trump supporter mailed pipe bombs to CNN and a handful of big-name Democrats. The day the news broke, my wife jokingly chatted me, “Now might be a good time to get that gun.”

When I finally made the purchase, I opted for a Smith & Wesson M&P 9 mm, a semiautomatic handgun I’d tried at the range. The M&P refers to the military and police units to whom the pistol line was originally marketed, an association I found suitably objectionable for the purposes of my project. The day I brought it home, I was already prepared to relinquish it. I bookmarked the “Voluntarily and Peaceably Surrendering a Firearm” page on the Metropolitan Police Department’s website, eager for the day when I could store a useless bundle of unidentified cables in my coffee table instead.

As time went on and different coverage priorities emerged, my gun piece fell off my to-do list. I forgot about the firearm in my living room for months at a time. Occasionally, though, it resurfaced. On Jan. 6, 2021, when right-wing protesters stormed the U.S. Capitol—which we can see from our back deck—my wife wondered aloud if we should take out the firearm and keep it on the table by our front door, just in case.

The idea didn’t seem entirely paranoid. On TV, we were watching violent mobs in our city beat down police officers, climb walls, and crash through windows, chanting their intent to hang the vice president. We had no idea how far the riot would go. Parked on the streets around our house were a couple of out-of-state vehicles covered in menacing stickers, presumably belonging to demonstrators who would return to them in who-knows-what state of postrebellion fervor.

I told my wife that threatening hyped-up insurrectionists with an unloaded gun—when whatever they might be carrying would surely be loaded and wielded with skills superior to mine—was a reliable way to get killed. I was already humiliated by the potential headlines: “Pistol-Waving, Coastal Elite Lesbians Offed in One-Sided Firefight, Seemingly Unaware That Guns Require Bullets.” We shut our blinds instead, and kept the handgun hidden away.

It’s impossible to know how many LGBTQ+ people own firearms, but the data that does exist shows queer people keeping guns in much lower numbers than heterosexuals. According to a 2018 report from the Williams Institute at the UCLA School of Law, 19 percent of lesbian, gay, and bisexual American adults have a gun at home, compared to 35 percent of straight people.

The sociodemographic explanations for the gun gap are easy to fill in. Openly LGBTQ+ people tend to be younger, more progressive, and slightly likelier to live in urban areas than the average American, all of which correlate with lower rates of gun ownership. But ever since Trump’s first presidential win, surveys and reports have chronicled a rising interest in guns among left-leaning demographics. The Liberal Gun Club saw a bump in membership after the 2016 election. Black voters reporting gun ownership in their households spiked from 24 percent to 41 percent between 2019 and 2023, while the percentage of white voters saying the same rose just 3 points.

Discords and subreddits for queer and trans gun enthusiasts have boomed, especially as anti-LGBTQ+ violence has proliferated. In 2024, hate crimes targeting trans people were up 31 percent from 2021, and those targeting gay and bisexual people were up 14 percent. That year’s tally—1,950 crimes based on sexual orientation and 463 based on gender identity—was second only to 2023’s in all FBI-recorded history. Right-wing and white-nationalist agitators have become an increasingly reliable presence at Pride festivals and drag events, casting an intimidating pall over spaces that once seemed like safe havens.

This has all come amid a mounting assault on the rights of women and trans people to make their own medical decisions and govern their own lives. In May 2022, in response to the news that the Supreme Court was planning to overturn Roe v. Wade, one of the most famous trans women in the U.S. issued a call to action. “If you are able to afford it, and if it is safe for you to do so,” Chelsea Manning wrote online, “you should consider arming yourselves, then finding others to train with in teams and learn how to defend your community—we may need these skills in the very near future.”

Others have likewise framed LGBTQ+ firearm ownership not as a value-neutral option, but as a responsibility. Earlier this year, signs wheatpasted around Baltimore advised passersby to “buy a gun” above an illustration of the transgender flag poking out from the barrel of a pistol. “You only lose the rights you are not willing to defend,” it read. “Inaction is a choice. Do not wait for it to be made for you.”

Some Republicans have used this shift in rhetoric to stoke anti-trans animosity, spreading vicious and easily debunked rumors about the prevalence of trans killers. After a transgender woman killed two children and injured many more at a Minneapolis Catholic church last year, the Department of Justice began looking into ways to curtail trans Americans’ right to own firearms. (I am forced to hand it to the NRA, which stood on business to oppose the proposal.)

The shift in my own social circles came suddenly, after Trump’s reelection, in 2024. For the first time, people who’d been bewildered and low-key disturbed by the choices of our friend Roxanna (a pseudonym), a lesbian who keeps a safe filled with firearms in her home just across the Maryland border, were asking for her advice on emergency preparedness. (She was more than equipped to provide it.) Several queer friends who had never expressed a prior interest in guns began taking classes to learn how to use them.

One friend, Shane (also a pseudonym), who is transfeminine and nonbinary, once told me they’d never want a gun in their house. Their position has since changed. Last year, they purchased a 3D printer chosen specifically for its ability to make filaments that can be used to build a gun, just in case the political situation gets worse. As right-wing political leaders portray trans people as malicious or mentally ill sex criminals, Shane worries that they might be clocked as trans on the street and attacked, or followed home after using a public restroom. “It would not at all surprise me to see a fairly public and unbridled lynching of a trans person in the next year,” they said.

Shane has always supported stricter gun-control legislation, but they’ve come to the conclusion that America is unlikely to ever pass it. And if the country is overrun with firearms for the foreseeable future, “I am not interested in only people who think I shouldn’t exist having guns,” Shane said. They still don’t believe that guns keep people safe, even when kept for self-defense, “but when safety has been taken away, it can give you power.”

Sometime last spring, as the daily escalations of the Trump administration sent my mind spiraling, I realized that I’d stopped thinking of the gun stashed in my coffee table as a loathsome liability and started considering it a potential asset. A whole new set of disquieting possibilities felt as if they were opening up before me: mass civil unrest, white-nationalist militias welcomed by the president, an attack on D.C. If any of the worst came to pass, I thought, it could be useful to have this tool at my disposal.

Since I hadn’t touched my gun in six years, I made an appointment for a firearms refresher course at a shooting range in Virginia. When I arrived on a Thursday afternoon, I was instantly reminded of how, aesthetically and politically, gun culture and gay culture are at odds. A giant “Trump Vance” sign loomed over the parking lot; another one read “Only Jesus can save America.” My instructor, who resembled RFK Jr. with a goatee, smirked when I told him I made a living as a journalist. “I’ll try not to judge,” he said.

As we walked to the outdoor range, fake RFK presented me with a pair of pink earmuffs for hearing protection. I commented on the color, and he said he’d hoped I wouldn’t be offended, but he’d had to choose between pink or blue. “It’s like a gender-reveal party for my ears,” I joked. The instructor grinned. “We just had one of those yesterday,” he said.

Despite his enthusiasm for the gender binary, my guy had a welcoming presence, clearly thrilled to spread the gospel of gun ownership to all comers, even me. When he inquired about my home life, he referred to my “husband, wife, whatever”—a phrasing several degrees more affirming than what my wife and I sometimes get at hotel check-in desks. He also confirmed that when I racked the slide, I looked “so Hollywood.” My Mariska Hargitay complex gained strength.

Despite my lengthy neglect of the firearm, my aptitude hadn’t faded. Hitting bull’s-eye after bull’s-eye in the golden-hour sunlight, I felt unstoppable. RFK was impressed. The barest hint of a fantasy materialized in my head: holding my own in a queer militia, taking down an assailant bent on harming us, maybe nabbing some squirrel meat for the campfire.

My path from fearing guns to understanding their appeal is a common one. My friend Roxanna, the one with a small arsenal in the D.C. suburbs, grew up with federal-worker parents who never talked about guns. The first time she touched one, a little over a decade ago, she said, “I felt like I was holding, like, toxic waste in my hands—like if I made one small mistake, I was going to kill everyone around me.” But after Roxanna joined co-workers on a trip to a gun range, she started to enjoy shooting as a form of stress release. Now she owns five guns of her own.

She bought her latest last summer, a small, wearable semiautomatic for self-defense. In the Trump 2.0 era, she felt validated in her decision by a chilling bit of reporting she’d come across in an 1892 pamphlet by Ida B. Wells. Very few proposed lynchings of Black people had been averted that year, Wells wrote: “The only times an Afro-American who was assaulted got away has been when he had a gun and used it in self-defense.”

When Roxanna thinks about circumstances that might make her reach for a gun, she envisions MAGA mobs inciting mass civil unrest. Or, if the country devolves into deep authoritarianism, she and her wife will want protection as they flee to a sanctuary state or Canada. There’s also the remote possibility of some kind of mass roundup that would find armed government agents knocking at her door. I expressed doubt that Roxanna and her wife, a peacenik fashionista, could successfully fend off the Gestapo should they arrive. “Probably not, but they’re not going to take my Black ass alive,” she said. “I’m not going back to a plantation, and I’m not going to a concentration camp.”

A few days after my afternoon with RFK, I drove to an indoor gun range near Baltimore for a gathering of the D.C. and Maryland chapter of the Pink Pistols, an LGBTQ+ shooting group. Founded in 2000, with dozens of chapters across the country, the organization advocates for looser gun restrictions and provides opportunities for new gun users to learn to shoot. Pink Pistols also tries to spread the word that our people are no longer easy targets, because some of them are carrying concealed weapons. Its motto: “Armed Queers Don’t Get Bashed.”

Wayne Lerch, 67, co-founded the D.C. and Maryland chapter in 2022. For two years, it was mostly just him and two other guys in a Facebook group, posting up at a couple of lanes at the shooting range for occasional meetups. That changed with Trump’s election that November. Within months, the chapter drew hundreds of new Facebook group members. The meetups grew so popular that they now rent out the entire range every month for 15 to 25 people, many of them brand new to guns. Lerch estimates that up to 70 percent of the newcomers are trans. “A lot of them have not wanted anything to do with firearms before,” he said, but now feel “it’s necessary to get involved.”

When I joined the range day on a Sunday morning in May, about 15 people were gathered at the venue, listening to a safety briefing. A few sported attire that amended gun culture with homosexual flair: a set of protective earmuffs topped with pink cat ears; a shirt that read “My Little Pew Pew” above a pony with a handgun “cutie mark”; a patch on a gun case depicting an AR-15 over a trans flag and the words “Defend Equality.” The group was a bit awkward but friendly, eager to commiserate about the anxieties of living under Trump 2.0. About a third of them had never shot a gun before.

Once we took our places at the shooting lanes, the room erupted in controlled explosions. Gold bullet casings flew through the air, littering the ground like confetti on a dance floor. It was unlike any other queer mixer I’ve attended.

Still, the vibe wasn’t not flirty. One woman, an Air Force member who was there with her wife and a co-worker, approached me as I took a break between rounds and leaned in close so I could hear her over the gunfire. “I’m guessing you’ve done this a lot,” she said. “You walked up there like a pro.” I decided not to correct her. She told me her crew was trying out shooting for the first time—mostly for fun, but also thinking it might be a “good skill to have” in this moment.

Even Lerch, the Pink Pistols chapter coordinator who now works as a safety officer at the range we visited, is no longtime gun fanatic. He got interested around the time Trump entered the White House in 2017, when he felt newly vulnerable as an openly gay man in D.C. “Seeing Proud Boys and Christofascists running around my town, I started getting worried about my own safety,” he said. Under the guidance of a conservative friend, he purchased a gun for self-protection and developed a love of shooting. He’s even gotten into target competitions and long-range rifles. “Hearing that steel ring at 500 yards—I can’t describe it. It’s just an amazing feeling,” he told me.

Talking to Lerch and others that day, I was reminded of the reporting I’d done on left-leaning groups that had ballooned with newly minted activists during Trump’s first presidency. Those were individuals who still had faith that the system would work according to a set of preestablished rules, and that well-meaning people could make a difference. Now boatloads of left-leaning Americans have been driven to try something new in response to political outrage and fear. It is different from most anti-Trump activism, which tries to appeal to common American values and use the tools of democracy for political change. Guns are a personal answer to a collective problem. They embody a turning inward, a desire to look out for oneself rather than engage in the messy, corny, frustrating work of trying to make society better for everyone.

For many new LGBTQ+ gun owners, an embrace of firearms is not an expression of deeply held values but an abandonment of them—a capitulation to the worldview of institutions bent on our defeat. To whatever extent LGBTQ+ people are picking up guns in this moment, it speaks to their waning confidence in queer political power. American democracy no longer holds the same promise of potential progress.

So, in the absence of hope, there is resignation. The country is full of bigoted people who exhibit no concern for the welfare of anyone but themselves. They also happen to be stocked with deadly weapons. If we can’t beat them, we might be tempted to join them.

For the seven years that I’ve now owned a gun, I’ve used one fact to reassure friends, and myself, that it’s safe to be around: I don’t keep bullets in the house. Whenever I’ve bought ammunition, it’s been at a gun range, and I’ve used it all up before leaving.

In this arrangement, my gun seems inert and irrelevant to my life, like a snowboard in a Miami condo. Having bullets at home would take me into territory so foreign it would feel like an identity shift: from an incidental gun owner to a potential gun user. In the concealed carry class I took before I bought my 9 mm, the gun instructor told us never to point a gun at something we weren’t willing to shoot. It was a simple hallmark of firearm safety, but it made my skin prickle. As I’ve spent more time using my weapon, testing its lethal power on sheets of paper, I’ve asked myself whether I could ever bring myself to use it outside the range. What would I conceivably point my gun at? Who am I willing to shoot?

The prospect is sickening to me, but also seductive. Having an instrument of death that could make an assailant shit their pants might be a decent substitute for stability right now. Any potential use case for a gun still sounds like morbid make-believe, but so would have half the things in the news this week if we’d heard them three years ago.

The fantasy embedded in queer firearm ownership is of a total transformation of self, from victim of circumstance to ready combatant. In reality, though, this wave of new LGBTQ+ gun owners seems likelier to result in a wave of accidental gun deaths. A Washington Post article published last February profiled a trans woman who bought her first firearm after Trump’s reelection and now “demonstrates how to safely handle firearms for her friends.” In one of the photos accompanying the piece, she is depicted in her living room, flanked by trans pals, with her finger on the trigger of her revolver—a position every responsible gun owner knows not to adopt, even with an unloaded weapon, until ready to fire. It scares me to think of people bringing guns to queer events, believing they’re protecting the community when they’re actually putting us at risk.

I am also tormented by the death of Alex Pretti, shot in Minneapolis by ICE agents who may have been agitated by the gun Pretti carried on his waistband. The gun was legal and permitted, and Pretti made no moves to threaten the agents with it. They killed him anyway. His firearm offered no defense. Members of Trump’s personal militia clearly don’t need the excuse of a gun to justify killing a dissident, but neither would I want to give them one in their current state of trigger-happiness. It’s tempting to envision my gun solely in defensive contexts, when it could just as easily be a useless prop or, worse, a provocation.

It also bears mentioning that handgun ownership is associated with dramatically higher rates of suicide—more than three times as high for men and seven times as high for women. LGBTQ+ people are already at greater risk of self-harm. These statistics were ringing in my head as I read that Washington Post article, in which the new gun owner explained the rise in gun interest among her trans peers thus: “If our hormones are taken away, we’d rather just kill ourselves.”

This isn’t idle musing. One trans woman who offers free firearm courses to other trans people sells a patch in her online shop that bears the Latin translation of an increasingly popular phrase, “Death Before Detransition.” Meanwhile, prominent Republicans are trying to ban gender-affirming care for trans people of all ages, and affordable mental health care is hard to come by. I would never tell a trans person seeking a sense of safety to forgo a firearm if they want one. But I don’t love the idea of encouraging a population at high risk of suicide to load up on death machines at a moment of community crisis.

As for my own gun, I’m more worried about the potential for an accident, and for good reason: Tens of thousands of people suffer unintentional firearm injuries in the U.S. each year. Hundreds die. If I brought bullets into my home for the purposes of self-defense, I’d have to commit to regular training to be anything but a danger to myself and everyone around me. My RFK-look-alike gun instructor recommended going shooting twice a month to be a safe and skillful gun owner. Twice a month! There are people I consider my close friends whom I don’t see that often.

I came to an inflection point in my gun journey the day Charlie Kirk was killed. After I learned he’d been shot—his alleged shooter had texted “Some hate can’t be negotiated out” to a roommate and possible partner, referring to Kirk’s anti-trans rhetoric—I struggled to imagine what might come next. For a moment, I was glad to have my gun. It felt like a security blanket as I worried about escalating political violence and calls for retribution against the left. But as my social feeds surfaced video after nauseating video of the shot that killed him, I lurched toward the opposite conclusion. The reality of gun violence is so gruesome, so devastating, so antithetical to a good human life. I could not watch that video and visualize myself behind a gun.

It got me thinking about one of the only case studies we have of someone actually stopping a violent assault on a queer event. In 2023, 45-year-old Richard M. Fierro was watching a drag show at Club Q, in Colorado Springs, when a man came in and shot 24 people, killing five. He might have killed more had Fierro not tackled, disarmed, and restrained him. Though Fierro is an Army veteran, which he credits with his combat instincts, he had no weapon on hand. Still, he subdued the shooter, likely saving lives in the process.

If I’m going to spend precious hours of my life learning skills for a future in peril, I’d rather they be Fierro’s. In countless real-life scenarios, pepper spray, de-escalation tactics, or a tourniquet would be more useful than a quick-drawn pistol. These are things I could readily integrate with my existing identity without the sense of forsaking my own humanity. The person I want to be in this era of persecution and conflict is one who mitigates harm, not inflicts it.

And yet—the 9 mm still sits in my living room.

I no longer need it for a work assignment. All I would have to do is call 311, and a D.C. police officer would come to take it away. But every time I entertain that option, I get stuck. The firearm is a ghastly contradiction: It terrifies me, and it brings me comfort. The very thing that makes it terrifying is also what makes it feel like an instrument of safety.

Will I ever take that next step and buy a box of bullets? I don’t know, and I’m not entirely certain what my tipping point would be. I hope and believe it will never come. My gun is a depressing admission that our society is trending against my well-being. Statistically and symbolically, it brings me one step closer to death. I’m still not ready to give it up.